On our infinite appetite for distraction...

Hey everyone,

I've been thinking a lot lately about 'Infinite Jest' by David Foster Wallace and its central idea of us being infinitely pleased by endless entertainment. I also like Father John Misty's (much shorter!) song-version 'Total Entertainment Forever.' In a similar vein the wise Mitchell Kaplan, award-winning bookseller behind the wonderful Florida indie bookstore chain Books & Books, tipped me off years ago to the book 'Amusing Ourselves To Death' by Neil Postman (1931-2003). The title once again telegraphs the idea and I'm sharing Neil's masterfully pithy Foreword below.

May we all continue to observe and intentionally turn off our blaring screens. May we continue to read books. May we find steadiness in friendships that have lasted through the slushy slurry storms of today. May we continue to observe the entertainmentification of information for what it is while also— somehow, some way—balancing contemporary whats-happenings with longer, deeper, richer pursuits.

Please enjoy the short 336-word introduction to Neil Postman's 1985 classic 'Amusing Ourselves To Death.'

Neil

Amusing Ourselves To Death: Foreword

Written by Neil Postman

We were keeping our eye on 1984. When the year came and the prophecy didn’t, thoughtful Americans sang softly in praise of themselves. The roots of liberal democracy had held. Wherever else the terror had happened, we, at least, had not been visited by Orwellian nightmares.

But we had forgotten that alongside Orwell’s dark vision, there was another—slightly older, slightly less well known, equally chilling: Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Contrary to common belief even among the educated, Huxley and Orwell did not prophesy the same thing. Orwell warns that we will be overcome by an externally imposed oppression. But in Huxley’s vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity and history. As he saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distractions." In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.

This book is about the possibility that Huxley, not Orwell, was right.

Postman hits exactly how I feel about the algorithm.

How are we amusing ourselves to death today? Jonathan Haidt goes deep on the dangers of social media in our interview on 3 Books.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

Joy in Dark Times

Hey everyone,

I hope you and your loved ones are healthy these days. Grief comes up in so many ways—so many places. Love and energy to those of you in California. For Leslie and I, we've had a couple friends and family members get challenging diagnoses recently. Grief does seem to help pull what's important to the surface.

Our friend Clare shared she's been finding solace in a book called 'Wild Hope: Healing Words To Find Light On Dark Days' by Donna Ashworth (@donnaashworthwords). Leslie bought the book and we loved the first poem Clare texted us which is called 'Joy Chose You.'

I hope it resonates with you too,

Neil

Joy Chose You

Written by Donna Ashworth

Joy does not arrive with a fanfare

on a red carpet strewn

with the flowers of a perfect life

joy sneaks in

as you pour a cup of coffee

watching the sun

hit your favourite tree

just right

and you usher joy away

because you are not ready for her

your house is not as it should be

for such a distinguished guest

but joy, you see

cares nothing for your messy home

or your bank balance

or your waistline

joy is supposed to slither through

the cracks of your imperfect life

that’s how joy works

you cannot truly invite her

you can only be ready

when she appears

and hug her with meaning

because in this very moment

joy chose you.

Here's another poem that helps me focus on what's most important.

One of the best ways to be ready for joy? Practicing gratitude.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

Forget New Year's resolutions. Do this instead.

Happy New Year!

I hope you had a great 2024 and I'm looking forward to spending time together in 2025.

I know it's January 1st but I admit I'm not much of a New Year's resolution person. They don’t work for me! "Oh, the calendar flipped! Time to start yoga, lose 15 pounds, and stop drinking."

Yeah, right. Too big, too unrealistic! And it's not just me. According to the University of Scranton only 19% of people actually maintain their New Year’s resolutions and US News reports that 80% of all resolutions are dropped by February.

So what’s a better way to grow?

Well, it’s not about years. I say it's about months.

And it’s not about massive leaps. To me it's about little improvements. About constantly steering your ship the right direction.

I think a better way to grow is with a monthly dashboard.

What’s a dashboard?

You stare at one every time you start your car. The dashboard flashes signals to make sure your seatbelt is on, your high-beams are off, and you’re going the right speed.

Does the dashboard put your seatbelt on? Hit the brakes for you? No, of course not. You do that. The dashboard just provides real-time feedback to help you course correct along the way.

For the past few years I've written out a monthly dashboard. It’s got four focus areas on 12 things I measure with a green, yellow, or red circle each month. Green means I’m good! Yellow means I’m close. Red means I’m way off.

Part of what’s great about a dashboard is that it allows me to map out all the goals I have bouncing around in my head. A study by Gail Matthews, psychology professor at Dominican University, found that people who write down their goals and dreams on a regular basis are 42% more likely to achieve them. The manifesting effect!

The goal isn't to be perfectly green each month.

It's just to see which areas of my life need focus and then course correct along the way.

And my dashboard isn’t fancy! I write it in marker on a piece of blank paper or in my notebook.

Here’s what my dashboard looked like last month:

The middle is my ikigai. I wrote "Help people live happy lives." An ikigai is your purpose, your high level goal, the reason you get out of bed in the morning. (I talk more about ikigais here and in Chapter 4 of 'The Happiness Equation.')

And then outside the ikigai: The top two boxes are what I do. The bottom two are how I do it.

I like the mental image of the bottom boxes actually supporting the top boxes.

So what do I do?

Strong Core

For me the core of my work is writing. So the first two things I measure are publishing one new article (on somewhere like CNBC or HBR) and writing one chapter of a new book. Writing, writing, writing! And a big way I get ideas into the world is through keynote speeches. That's the 4 speech goal I have each month. Doesn't always happen but last month I was green on all three.

Fastest learning

Next! Learning. What's the fuel for your core? My goals are to stay curious by reading 8 books a month, conducting 2 deep-dive interviews a month, and having 1 new experience a month. I publish my Monthly Book Club to keep the pressure on the reading. And the interviews? That's why I designed my podcast the way I have—I get to go deep preparing and publishing interviews with people like Brené Brown, Jonathan Franzen, and David Sedaris. And one new experience? Well, that's subjective of course, but it could be anything from putting all my books into the Dewey Decimal system, taking my son to his first Flaming Lips concert, or even just trying a type of cuisine I've never tried. Open ended! And lots of months I miss here. But the goal is to push myself to stay curious and expand.

Best family

This is the box missing from the corporate charts hanging at the office. Your best self starts at home. (I've written about the importance of family contracts before, too.) For me it means being away from home less than 4 nights a month, having 4 deep airplane-mode Family Days each month, and going on one Family Adventure together. Last month I was traveling a couple weekends which earned me a yellow and red on the dashboard.

Best self

We know how airlines say to put the oxygen mask over your mouth before putting it over your kid's. That would be hard for any parent! But the airlines know something we don’t: we're no good to anyone if we don't take care of ourselves. Best Self means taking care of you. I use an app called Trainiac to track my workouts, and my goal is to do 4 workouts a week and have 4 longer cardio sessions a week. 16 a month! You can see by all the red circles I didn’t do a great job last month! I hit my workouts (thank you, hotel gyms) but my cardio and Neil's Nights Out (NNOs, discussed in the family contract) took a hit.

So that’s it!

That’s my monthly dashboard.

There are a few things I love about the system.

First, it’s for me, by me. It’s not a hard-and-fast contract. It’s a system of course correction that lets me identify trends and make adjustments to my life. If I miss my cardio three months in a row, it’s time to think: do I need to sign up for hockey? What should I do to get this on track? Or should I just swap this wholesale for something else? Maybe it's time to fold back in meditation, volunteering, or music lessons. But if it’s red just one month, I know it was just a little bump, and I can aim to improve it as I go.

In our fast-paced, frenetic world months are the perfect time where you can roughly scratch out how you’re doing on a dashboard, take a minute to zoom out, and make course corrections along the way.

And as always let's remember:

The goal is not to be perfect here.

It's just to be a little better than before.

Here's to a great 2025!

A great way to motivate this kind of monthly action is through moonshot goals.

If you're stuck figuring out what to focus on, think about the 3 S's of success.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

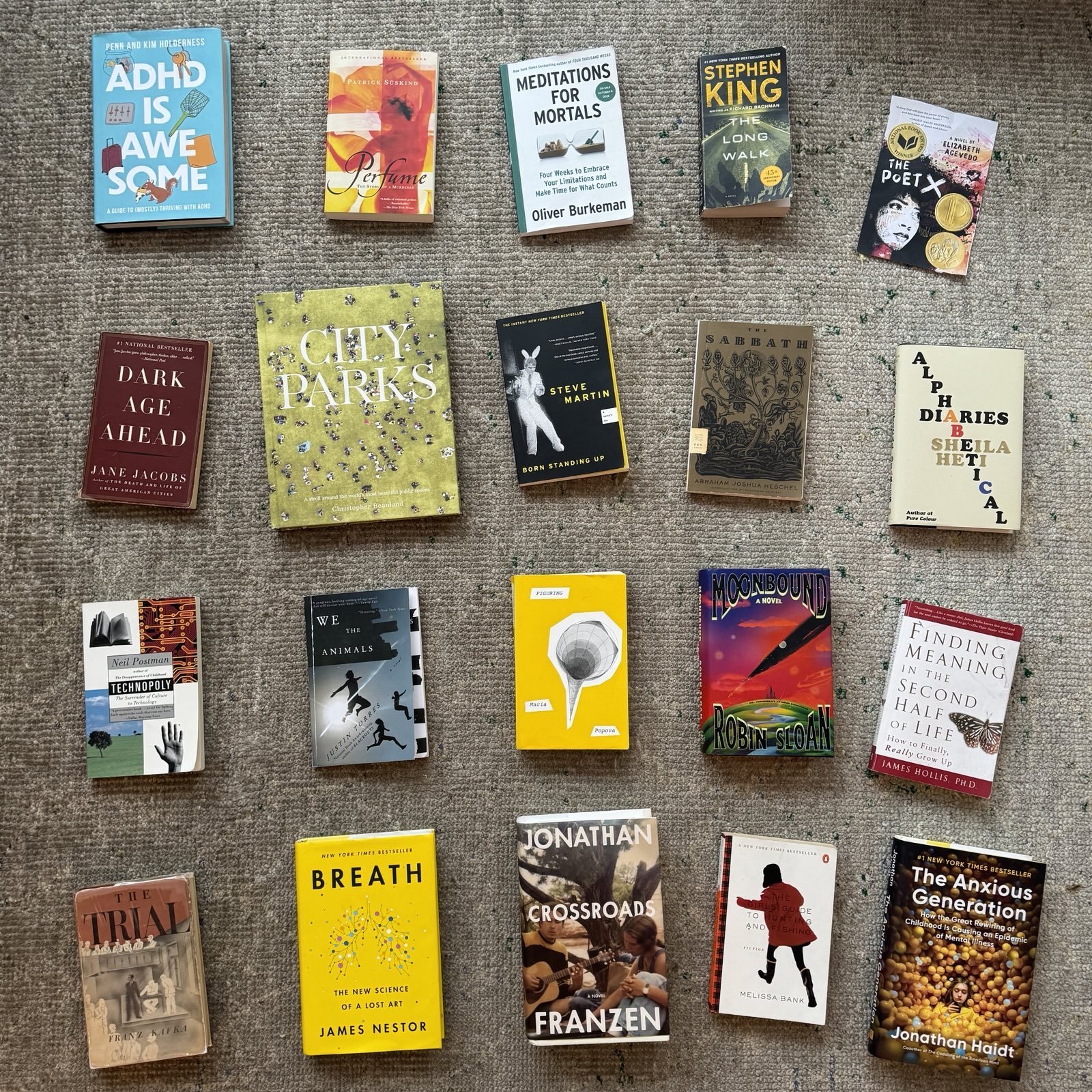

The Very Best Books I Read in 2024

Hey everyone,

Here are the Very Best Books I Read in 2024.

As always the book titles click over to link splitters that take you to links to the library, indie bookstores, and, of course, Barnes & Noble, Indigo, and Amazon. I get zero commissions from any of them. Buy from wherever you like!

Also, here are the Very Best Books I Read in 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, and 2017, too.

I’ll be back with our “Best Of 2024” episode of 3 Books on the Winter Solstice (December 21!) and my next Book Club in January.

Happy holidays,

Neil

PS. Invite others to join us here.

20. ADHD IS Awesome: A Guide To (Mostly) Thriving With ADHD by Penn and Kim Holderness. I just read this book last month and can’t shut up about it. A collection of everything we know about ADHD, written by an ADHD brain, for an ADHD brain. Penn writes that “a typical person with ADHD will have challenges with listening, completing tasks, and keeping track of time (and possessions). They’ll be restless, always ‘on the go’, talkative, and impatient.” Sound like anyone you know? The new ADHD classic.

Perfect for: anyone who thinks they might have ADHD, anyone who loves someone with ADHD, neuroscience and neurodiversity fans…

19. Perfume: The Story of a Murderer by Patrick Süskind. By far the most sensory book I read this year. I read it in January and can still smell its smells. The book takes place in France in 1738 when “The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots.” He endlessly does this: olfactory yanks you right into a scene. Tells the astounding story of poverty-stricken, nasally-gifted, slumdog-orphan Jean-Baptiste Grenouille from his birth in 1738 to his death in 1766. A zero-to-hero-to-zero-to-I-won't-ruin-the-ending tale that will amaze, disturb, and awe. Good books rattle from the inside. This is a rattler. Sold over 25 million copies before its author became a recluse. (Feel free to skim “the back of the book” via the Plot Summary on Wikipedia first.)

Perfect for: people who like challenging fiction, nonjudgemental dopamine seekers, anybody who wants to time travel to 1700s France…

PS. Celine Song, filmmaker of ‘Past Lives,’ said this was one of her 3 most formative books. Listen to us discuss the book and how she uses sensory deprivation to create chemistry on YT/Spotify/Apple.

18. Meditations for Mortals: Four Weeks to Embrace Your Limitations and Make Time for What Counts by Oliver Burkeman. The perfect “New Year, New You” book for 2025. Oliver reminds us time is finite (“…you’ll never feel fully confident about the future, or fully understand what makes other people tick — and that there will always be too much to do) and reminds us that’s okay—that’s normal! that’s right!—because “being a finite human just means never achieving the sort of control or security on which many of us feel our sanity depends”. He shares 28 short 3-5 page essays meant to be read once a day over four weeks and invites us to approach the book “as a return, on a roughly daily basis, to a metaphorical sanctuary in a quiet corner of your brain, where you can allow new thinking to take shape without needing to press pause on the rest of your life.”

Perfect for: people into healthy cognitive fitness, anyone looking to reduce self-criticism, fans of pithy eloquent wisdom in the vein of ‘The Art of Living’ by Epictetus (12/2016)…

PS. I interviewed Oliver on the Wolf Moon. He gives a writing masterclass and shares the unique way he captures ideas. Listen on YT/Spotify/Apple.

17. The Long Walk by Stephen King. This is ‘The Road’ by Cormac McCarthy (2/2017) meets ‘The Hunger Games’ by Suzanne Collins, except written decades before either of those. This book is to those like The Pixies are to Nirvana or Nirvana is to Weezer. It’s a newly reprinted original Richard Bachman from 1979. King wrote it when he was 30. The book takes place in a slightly dystopian near future where 100 sixteen-year-old boys from across the US apply each year to be selected to begin “the long walk” which starts on foot in Maine and ends when there is only 1 boy left. Anybody who stops longer than a couple long pauses is immediately shot and killed and dragged off the road. The whole book is the by turns simple, vulgar, and entrancing conversation between the boys during the walk, all told in a seductive first-person-y third-person following Ray Garraty, pride of Maine, who leaves his girlfriend and gets dropped off by his mom as the book opens. Nothing grotesque in the book! Nothing gruesome, nothing jumping out of the forest. It’s more thrilling than scary.

Perfect for: anyone looking for a beach read, anybody looking to get back into reading, general Stephen King fans or any Stephen King fans who haven’t read the Richard Bachman stuff…

16. The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevédo. A 2018 coming-of-age YA book about a Dominican teen girl in Harlem falling in love, losing and finding God, navigating relationships at home and school, and discovering her poetic voice. Slam-poetry flow with Acevédo’s beautiful voice: “Walking home from the train I can’t help but think Aman’s made a junkie out of me—begging for that hit, eyes wide with hunger, blood on fire, licking the flesh, waiting for the refresh of his mouth. Fiend, begging for an inhale, whatever the price, just so long as it’s real nice—real, real nice—blood on ice, ice, waiting for that warmth, that heat, that fire. He’s turned me into a fiend, waiting for his next word, hanging on his last breath, always waiting for the next next time.”

Perfect for: fans of YA, fans of Nicola Yoon or John Green, and anybody looking to sprinkle a bit of melody into their life…

15. Dark Age Ahead by Jane Jacobs. The New York Times called Jane Jacobs a “writer and thinker who brought penetrating eyes and ingenious insight to the sidewalk ballet…” and she may be most famous for her 1961 classic ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities.’ This book was written much later—when Jane was 88 in 2006, the last year of her life—and in it she speaks with wisdom about all cultures hitting Dark Ages—from the Roman Empire in the fifth century, to the Islamic Empire in the fifteenth, to ancient Chinese Empires that (I learned) ruled the seas 500 years ago—sending 400-foot long ships holding up to 28,000 (!) sailors to Africa decades before Columbus sailed the ocean blue. “Centuries before the British Royal Navy learned to combat scurvy with rations of lime juice on long sea voyages,” she writes, “the Chinese had solved that problem by supplying ships with ordinary dried beans, which were moistened as needed to make bean sprouts, a rich source of Vitamin C.” But then what? Dark age. New political party halts voyages, dismantles shipyards—skills are lost over generations. She has a powerful refrain: we can’t assume what we have won’t slip away and we need to actively strive to make things better. The five sections are “Families Rigged To Fail,” “Credentialing Versus Educating,” “Science Abandoned,” “Dumbed-Down Taxes,” and “Self-Policing Subverted.”

Perfect for: geography and urban planning folks, anybody looking for a big zoom out from US politics, and fans of perfectly poised writing…

14. A stroll around the world’s most beautiful public spaces by Christopher Beanland. What do I suggest after the dark warnings of our potentially crumbling civilization? A giant coffee table book about parks, of course! “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot,” sang Joni Mitchell in ‘Big Yellow Taxi,’ and sometimes walking around Toronto these days you can almost feel the grass screaming. If you live somewhere they’re paving over then this book is like a big breath of fresh air. From Central Park in New York to Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, this is a striking book full of love and hope.

Perfect for: park lovers, Nature Deficit Disorder-havers, people who wish the coffee table book about coffee tables was real…

3. Born Standing Up: A Comic’s Life by Steve Martin. This is the 2007 memoir by then-62-year-old Steve Martin. With short, tight, punchy sentences Steve tells an honest story of what might seem like a relatively benign life ordering magic tricks out of the back of a magazine and getting a job at the joke shop and, later, having panic attacks on weed and reconnecting with his family. But nothing sounds benign through Steve Martin’s lens. Tightly squeezed, highly concentrated, and double-spaced with lots of photos so the 204 pages feel breezy. Highly recommended.

Perfect for: anyone navigating the inner dynamics of public attention, aspiring stand-up comics, and memoir fans…

12. The Sabbath by Abraham Joshua Heschel. I grew up in the Toronto suburbs in the 1980s and it was agreed: Sunday was family day, rest day, church day, reflection day. “Gallantly, ceaselessly, quietly man must fight for inner liberty,” writes Abraham Heschel in this slim, 73-year-old interpretation and explanation of the Sabbath, the traditional Jewish day of rest from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday. I like the idea. I say bring it back! “Inner liberty depends upon being exempt from domination of things as well as from domination of people.” Yes! A slim 100 pages with a thick, dense, unfurling feeling like some kind of deep-in-the-jungle fern. “The solution of mankind’s most vexing problem will not be found in renouncing technical civilization, but in attaining some degree of independence from it.” (Pairs well with ‘The Technopoly’ by Neal Postman, which I mention later.)

Perfect for: self-help fans, someone you love who works too hard, anybody interested in using ancient wisdom and history to help with their lives today…

PS. This is one of Cal Newport's most formative books. You can list to our deep conversation about how he carves out time for rest while still getting things done on YT/Spotify/Apple.

11. Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti. This is not a book. It is a piece of modern art … wrapped in a book. Sheila Heti, author of ‘Pure Colour’ and ‘Motherhood,’ typed up 500,000 words from a decade’s worth of journals in rows of Microsoft Excel, kept them all in their original ‘sentence form’ but ignored all paragraphs and dates, then sorted all the sentences … alphabetically, and then carefully took out 90% of them. All that remains is the brave, daring, vulnerable, tender, funny, sexy silhouette-y statue of a young, literary, sensual woman growing up in the city.

Perfect for: enlightened bathroom readers, people who love ‘books as art,’ and general fans of the bildungsroman…

10. Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology by Neil Postman. A prophetic 30-year-old manifesto about the dangers of pervasive technology that helps illuminate so many of the algorithm and AI conversations we’re having today. The book opens by saying, yes, of course, technology gives us great riches, unfathomable riches, but that it also takes something away. (He excerpts a fascinating couple of 95-year-old paragraphs from Freud.) Postman then says “once a technology is admitted, it plays out its hand; it does what it is designed to do. Our task is to understand what that design is – that is to say, when we admit a new technology to the culture, we must do it with eyes wide open.” The book was written in 1992 but feels like it was written tomorrow. Casts that wide a timescale. Sample sentence from page 10: “In introducing the personal computer to the classroom, we shall be breaking a four-hundred-year-old truce between the gregariousness and openness fostered by orality and the introspection and isolation fostered by the printed word.” A short 199 pages that serves as a flying-through-time-portrait of our historical relationship with technology and potential implications for our cultures, communities, and relationships as we all fly together at warp speed.

Perfect for: reflective tech users, readers of Cal Newport and Jonathan Haidt (see #1), parents worried about cell phones in classrooms…

9. We The Animals by Justin Torres. My friend Jonathan texted me last week saying “Been getting into fiction this year, whole new world for me.” He told me he was listening to ‘Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow’ (Best Books of 2023) and asked what to read next. I suggested this. He wrote back a couple days later: “We the Animals just arrived, excited to dive in this week. Quite the list of mega reviews” and then the next day “Read half last night, will finish today. That there is some fierce raw writing.” Fierce! Raw! Yes, those are the two words that come to mind. A silhouette of three young boys Peter Panning across the sky graces the cover of this debut novel by Justin Torres (b. 1980) which contains nineteen short, unnumbered chapters that hit a near-impossible high bar for pace and electricity. It opens frenetically: “We wanted more. We knocked the butt ends of our forks against the table, tapped our spoons against our empty bowls; we were hungry. We wanted more volume, more riots. We turned up the knob on the TV until our ears ached with the shouts of angry men. We wanted more music on the radio; we wanted beats; we wanted rock. We wanted muscles on our skinny arms. We had bird bones, hollow and light, and we wanted more density, more weight. We were six snatching hands, six stomping feet; we were brothers, boys, three little kings locked in a feud for more.” And doesn’t let up. This is the story of three brothers growing up. You are right there with the boys in fistfights, empty fields, cold basements, and inside sleeping bags on dim polished office floors. Exquisite, haunting, enchanting, lyrical, tough, raw, pure.

Perfect for: fans of evocative fiction, anyone with brothers, and people who like their serious fiction in 100-page instead of 1000-page doses…

8. Figuring by Maria Popova. “How, in this blink of existence bookended by nothingness, do we attain completeness of being?” That’s a question that comes up early in this book which ultimately zooms up to tell a fascinating history of arts and science told through deeply engaging and endlessly braided tales of the artists and scientists themselves. They’re not linear stories, though, because as she writes: “Lives are lived in parallel and perpendicular, fathomed nonlinearly, figured not in the straight graphs of ‘biography’ but in many-sided, many-splendored diagrams.” Many-sided diagrams astound of people like Johannes Kepler, Maria Mitchell, Rachel Carson, Emily Dickinson, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, told with an entrancing spell of Maria’s particular brand of poetic narrative with endless snips and clips of letters, speeches, and writings weaved in.

Perfect for: fiercely intelligent people, deeply humanist people, and macro-orthogonal thinking science buffs…

PS. Maria was my guest on 3 Books earlier this year. Listen to our conversation on valuing community over commodification and learn about her 3 most formative books on YT/Spotify/Apple.

7. Moonbound by Robin Sloan. This is the book I spent the most time with this year. It filled me, and continues to fill me, with so much twinkling rainbow wonder. The feeling of this book is like the front cover image above twisting into a kaleidoscope of images again and again and again. I fell into this book like almost nothing else and I simultaneously had no idea what was going on and couldn’t wait to find out what happened next. Talking beavers. Talking swords! Video games. Wizards, who aren’t really wizards. And the entire book is narrated by a microscopic AI-type chronicler, who’s been in many different lives across the millenniums, but who now sits in our protagonist’s left shoulder. Entrancing as the silence after the cymbal crash. I absolutely loved this book.

Perfect for: fans of ‘Cloud Atlas’ (6/2019) by David Mitchell, ‘Star Wars’ supernerds, people with an appetite for Willy Wonka on steroids type imagination…

6. Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life: How To Finally, Really Grow Up by James Hollis, Ph.D. Average lifespan right now is around 80 years. That means the second half of your life begins on your 40th birthday. Cue the mid-life crisis! Not so fast. Here comes poetically erudite Jungian analyst James Hollis to save you from that. Giant-minded with an in-the-clouds-and-on-the-street tone, this is a masterful l book I know I’ll be revisiting over and over. Hollis opens with a page of questions like “What gods, what forces, what family, what social environment, has framed your reality, perhaps supported, perhaps constricted it?” and “Why do you believe that you have to hide so much, from others, from yourself?” Biggies! Hollis quickly makes the argument that “In the end we will only be transformed when we can recognize and accept the fact that there is a will within each of us, quite outside the range of conscious control, a will which knows what is right for us, which is repeatedly reporting to us via our bodies, emotions, and dreams, and is incessantly encouraging our healing and wholeness.” Magnificent, deep, and soul-touching.

Perfect for: mid-lifers or anyone going through a transition, people who like to chew on deep questions, your friend who collects journals but never knows what to write about in them…

PS. This is one of Oliver Burkeman's (see #18) most formative books! Listen to Oliver talk about Jungian analysis and how Hollis has influenced him on on YT/Spotify/Apple.

5. The Trial by Franz Kafka. “No one’s got Kafka these days,” Patrick told me a few months back, petting his cat behind the counter at his underground used bookstore mecca Seekers. “Can’t keep him in stock. Nobody can. Hits too close to home these days.” Could that be true? No used bookstore in all of Toronto has anything written by the 1883-born Franz Kafka? I figured I had to buy Kafka used but I tried six stores before eventually caving in and going online to AbeBooks. This book is written in 1914 but sounds like a 100-year-in-the-future prophecy of our increasingly low-trust surveillance state. First sentence: “Someone must have been telling lies about Joseph K. for without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning.” Why? “We are not authorized to tell you that,” say the cops, one of whom, much later, is mercilessly beaten in a courtroom closet. This is a slowly-closing-in-on-all-sides tale of foreboding. Can you imagine being arrested by a remote, inaccessible authority, without your crime being revealed to you? Wonderfully paced, increasingly bleak book that has layers beyond layers and is just begging for a reread.

Perfect for: fans of classic literature, people who like movies that give them skin-crawling anxiety, students of writing…

PS. Jonathan Franzen talked about his relationship to ‘The Trial’ on 3 Books earlier this year. Listen on YT/Spotify/Apple.

4. Breath: The New Science Of A Lost Art by James Nestor. I have had this on my beside for three months now. I can’t stop flipping through it. This book is changing my sleep, my energy, my mood. I can’t recommend it enough for anyone interested in improving their body, their health, their vitality. You’ll be looking for your uvula in the mirror to assess your susceptibility for sleep apnea (“the Friedman tongue position scale”), buying mouth tape to tape over your lips at night (Nester recommends 3M Nexcare Durapore—I’ve been using it for 3 months and love it!), and even looking for tougher foods to chew, while practicing some of the breathholding exercises mentioned later. Read some of my favorite pages here.

Perfect for: people who never feel like they get enough sleep, failed meditators who need a more active practice, lovers of smart popular science books…

3. Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen. The first 400 pages of this book take place over literally one day. One day! And that day is December 23, 1971. That tells you what kind of detail you can expect here. Pulsing, messy, scabrous, erotic, reflective, breath-holdy, shocking, punchy, illuminating. Plot twists! Perfect dialogue! We follow the Hildebrandts—father Russ, mother Marion, four kids ranging from college-age Clem to high school social queen Becky to drug-dealing teen Perry to little, almost invisible Judson—as they navigate complex inner-outer lives around their church in the fictional small town of New Prospect, Illinois. Every chapter gives each character’s unique perspective and backstory until the slow-pounding 200-page fireworks display at the end. The characters might be dark—but there’s a humanity, a beauty, an inner-inner life, that Franzen exposes like almost nobody else writing today. ‘Crossroads’ will take you far, far away. A book to help us stare slack-jawed at something in ourselves while adding some taffy and fillings to the human experience.

Perfect for: anyone who enjoys family dramas, Franzen fans who liked ‘The Corrections’ or ‘Freedom’ but missed this one, people who like falling into 600-page novels…

2. The Girls' Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank. I never would have guessed at the beginning of 2024 that my favorite novel this year would be a coming-of-age romantic and sexual awakening first-person narrative from a snappy, turbo-charged Jersey-girl-turned-New Yorker through the 80s and 90s. But I loved it. A funny, fast-paced, emotionally sumptuous read with strong ‘When Harry Met Sally’ vibes throughout. Melissa Bank writes with a magical Claire Keegan (‘Foster,’ 9/2023) brand of writing I’d call “vivid sparsity.” The story is told through seven short stories that leapfrog through Jane Rosenal’s life with a wild unpredictability that feels like real life. An astounding life portrait told with speed, precision, zingers, and a rare three-dimensionalization. What a stunning voice!

Perfect for: people who like the fast paced funny-romantic feel of ‘When Harry Met Sally,’ fans who like Amy Einhorn books like ‘The Help’ or ‘Big Little Lies,’ people who want to live a whole life in a few hours…

1. The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness by Jonathan Haidt. A deeply clear, deeply researched, deeply, dare I say, obvious clarion call for no smartphones before high school, no social media before 16, entirely-phone-free schools, and a callback to open play for our kids instead of programmed safe-robot childhoods. (There’s even a three-page photo spread on old, dangerous playground equipment which was speaking my love language.) Get ready to smash your router with a hammer and take your kids to the park after reading how our social interactions have, for millions of years, been embodied, synchronous, one-to-one or one-to-several, with a high bar for entry or exit. Whereas now we have slathered ourselves so deeply digital that social relationships have become disembodied, asynchronous, one-to-many, with a low bar for entry and exit. No wonder we are lonely! (Which is, no biggie, worse for our health than smoking 15 cigarettes a day, according to this report from Surgeon General Vivek Murthy.) Tightly written, endlessly punctuated with charts, with every chapter nicely summarized with a perfect bullet point one-pager, this book is designed for max skimmability. You could honestly just flip past the 100 graphs and get the story. A rallying cry and anti-tech manifesto which offers new ways of living that look an awful lot like old ways of living. Here is part one of my highlights and here is part two. This book came out March 26, 2024 and in tomorrow’s December 8, 2024 New York Times Hardcover Nonfiction bestseller list the book is #6 with now 35 straight weeks on the list. In other words: WE HAVE LIFTOFF! Let’s keep pushing the movement forward. There’s a wonderful resource-filled site for the book, a phone-free school kit, a partnership with Dr. Becky to ‘free the anxious generation,’ and you can read up on what you can do as a parent, teacher, legislator, and more.

Perfect for: teachers and principals, parents of teens and pre-teens, and anyone worried about the unprecedented interference of technology…

Hermann Hesse on the Wisdom of Trees

Hey everyone,

I am trying to grow my zoom-out muscle. My looking at my life from far away muscle. I want to pull back against what the world pushes us towards—short! buzzy! trending!—and instead try and see more, do less, and remember the big things.

This is why I have a "rock clock" on my dresser: a little row of four smooth rocks pushed forward (for the four decades I've lived so far) and six rocks left pushed back (for the six decades I hope to live). I was inspired by the Clock of the Long Now which dongs once a year for 10,000 years. No matter what stresses I encounter during the day the rock clock is a reminder of the problem's teeny-tiny-ness relative to this broader decade. So maybe not worth stressing about?

I read a little excerpt by Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) recently that gave me this feeling. It's a poetic piece and I get something different out of it every time. These few paragraphs from Hesse's 1920 book 'Wandering' ultimately offers us a way of looking at ourselves as "life from eternal life" and reminds us to trust we are part of much bigger things—things we can't ever see—and so our most noble mission is simple being our truest selves.

Let's keep pulling back from the instant, the now, into our bigger and larger selves.

And may you see or touch a tree with love today.

Neil

The Wisdom of Trees

Written by Hermann Hesse

For me, trees have always been the most penetrating preachers. I revere them when they live in tribes and families, in forests and groves. And even more I revere them when they stand alone. They are like lonely persons. Not like hermits who have stolen away out of some weakness, but like great, solitary men, like Beethoven and Nietzsche.

In their highest boughs the world rustles, their roots rest in infinity; but they do not lose themselves there, they struggle with all the force of their lives for one thing only: to fulfill themselves according to their own laws, to build up their own form, to represent themselves.

Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree. When a tree is cut down and reveals its naked death-wound to the sun, one can read its whole history in the luminous, inscribed disk of its trunk: in the rings of its years, its scars, all the struggle, all the suffering, all the sickness, all the happiness and prosperity stand truly written, the narrow years and the luxurious years, the attacks withstood, the storms endured.

And every young farm boy knows that the hardest and noblest wood has the narrowest rings, that high on the mountains and in continuing danger the most indestructible, the strongest, the ideal trees grow.

Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life.

A tree says:

A kernel is hidden in me, a spark, a thought, I am life from eternal life. The attempt and the risk that the eternal mother took with me is unique, unique the form and veins of my skin, unique the smallest play of leaves in my branches and the smallest scar on my bark. I was made to form and reveal the eternal in my smallest special detail.

A tree says:

My strength is trust. I know nothing about my fathers, I know nothing about the thousand children that every year spring out of me. I live out the secret of my seed to the very end, and I care for nothing else. I trust that God is in me. I trust that my labor is holy. Out of this trust I live.

When we are stricken and cannot bear our lives any longer, then a tree has something to say to us : Be still! Be still! Look at me! Life is not easy, life is not difficult. Those are childish thoughts.

Let God speak within you, and your thoughts will grow silent. You are anxious because your path leads away from mother and home. But every step and every day lead you back again to the mother. Home is neither here nor there. Home is within you, or home is nowhere at all.

A longing to wander tears my heart when I hear trees rustling in the wind at evening. If one listens to them silently for a long time, this longing reveals its kernel, its meaning.

It is not so much a matter of escaping from one’s suffering, though it may seem to be so. It is a longing for home, for a memory of the mother, for new metaphors for life. It leads home. Every path leads homeward, every step is birth, every step is death, every grave is mother.

So the tree rustles in the evening, when we stand uneasy before our own childish thoughts : Trees have long thoughts, long-breathing and restful, just as they have longer lives than ours. They are wiser than we are, as long as we do not listen to them.

But when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy. Whoever has learned how to listen to trees no longer wants to be a tree. He wants to be nothing except what he is. That is home. That is happiness.

Spending time with the trees has science-backed benefits, too.

If you're heading to the woods, check out this interview with J. Drew Lanham to get excited about meeting the birds.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

Oliver Burkeman's eight secrets to a (fairly) fulfilled life

Hey everyone,

Oliver Burkeman is one of my favorite self-help writers. He takes a genre that can sometimes be full of pow-zam schlockiness and crafts it into something poetic and literary and deeply meaningful.

Oliver is our guest in Chapter 142 of 3 Books (Apple/Spotify/YT), which just dropped on last Friday's full moon, but he's been an influence on me for many years. In 2010 he wrote about my blog 1000 Awesome Things in his fifteen-year(!)-running Guardian column "This Column Will Change Your Life."

The very last column he wrote for The Guardian on September 4, 2020 is one I return to again and again. It's a deeply felt collection of timeless wisdom. Hope you enjoy it as much as I do and if you want to go deeper into Oliver's stuff check out his books 'Four Thousand Weeks' and 'Meditations for Mortals.'

Enjoy this beautiful week,

Neil

The Eight Secrets to a (Fairly) Fulfilled Life

Written by Oliver Burkeman

In the very first instalment of my column for the Guardian’s Weekend magazine, a dizzying number of years ago now, I wrote that it would continue until I had discovered the secret of human happiness, whereupon it would cease. Typically for me, back then, this was a case of facetiousness disguising earnestness. Obviously, I never expected to find the secret, but on some level I must have known there were questions I needed to confront – about anxiety, commitment-phobia in relationships, control-freakery and building a meaningful life. Writing a column provided the perfect cover for such otherwise embarrassing fare.

I hoped I’d help others too, of course, but I was totally unprepared for how companionable the journey would feel: while I’ve occasionally received requests for help with people’s personal problems, my inbox has mainly been filled with ideas, life stories, quotations and book recommendations from readers often far wiser than me. (Some of you would have been within your rights to charge a standard therapist’s fee.) For all that: thank you.

I am drawing a line today not because I have uncovered all the answers, but because I have a powerful hunch that the moment is right to do so. If nothing else, I hope I’ve acquired sufficient self-knowledge to know when it’s time to move on. So what did I learn? What follows isn’t intended as an exhaustive summary. But these are the principles that surfaced again and again, and that now seem to me most useful for navigating times as baffling and stress-inducing as ours.

There will always be too much to do – and this realisation is liberating. Today more than ever, there’s just no reason to assume any fit between the demands on your time – all the things you would like to do, or feel you ought to do – and the amount of time available. Thanks to capitalism, technology and human ambition, these demands keep increasing, while your capacities remain largely fixed. It follows that the attempt to “get on top of everything” is doomed. (Indeed, it’s worse than that – the more tasks you get done, the more you’ll generate.)

The upside is that you needn’t berate yourself for failing to do it all, since doing it all is structurally impossible. The only viable solution is to make a shift: from a life spent trying not to neglect anything, to one spent proactively and consciously choosing what to neglect, in favour of what matters most.

When stumped by a life choice, choose “enlargement” over happiness. I’m indebted to the Jungian therapist James Hollis for the insight that major personal decisions should be made not by asking, “Will this make me happy?”, but “Will this choice enlarge me or diminish me?” We’re terrible at predicting what will make us happy: the question swiftly gets bogged down in our narrow preferences for security and control. But the enlargement question elicits a deeper, intuitive response. You tend to just know whether, say, leaving or remaining in a relationship or a job, though it might bring short-term comfort, would mean cheating yourself of growth. (Relatedly, don’t worry about burning bridges: irreversible decisions tend to be more satisfying, because now there’s only one direction to travel – forward into whatever choice you made.)

The capacity to tolerate minor discomfort is a superpower. It’s shocking to realise how readily we set aside even our greatest ambitions in life, merely to avoid easily tolerable levels of unpleasantness. You already know it won’t kill you to endure the mild agitation of getting back to work on an important creative project; initiating a difficult conversation with a colleague; asking someone out; or checking your bank balance – but you can waste years in avoidance nonetheless. (This is how social media platforms flourish: by providing an instantly available, compelling place to go at the first hint of unease.)

It’s possible, instead, to make a game of gradually increasing your capacity for discomfort, like weight training at the gym. When you expect that an action will be accompanied by feelings of irritability, anxiety or boredom, it’s usually possible to let that feeling arise and fade, while doing the action anyway. The rewards come so quickly, in terms of what you’ll accomplish, that it soon becomes the more appealing way to live.

The advice you don’t want to hear is usually the advice you need. I spent a long time fixated on becoming hyper-productive before I finally started wondering why I was staking so much of my self-worth on my productivity levels. What I needed wasn’t another exciting productivity book, since those just functioned as enablers, but to ask more uncomfortable questions instead.

The broader point here is that it isn’t fun to confront whatever emotional experiences you’re avoiding – if it were, you wouldn’t avoid them – so the advice that could really help is likely to make you uncomfortable. (You may need to introspect with care here, since bad advice from manipulative friends or partners is also likely to make you uncomfortable.)

One good question to ask is what kind of practices strike you as intolerably cheesy or self-indulgent: gratitude journals, mindfulness meditation, seeing a therapist? That might mean they are worth pursuing. (I can say from personal experience that all three are worth it.) Oh, and be especially wary of celebrities offering advice in public forums: they probably pursued fame in an effort to fill an inner void, which tends not to work – so they are likely to be more troubled than you are.

The future will never provide the reassurance you seek from it. As the ancient Greek and Roman Stoics understood, much of our suffering arises from attempting to control what is not in our control. And the main thing we try but fail to control – the seasoned worriers among us, anyway – is the future. We want to know, from our vantage point in the present, that things will be OK later on. But we never can. (This is why it’s wrong to say we live in especially uncertain times. The future is always uncertain; it’s just that we’re currently very aware of it.)

It’s freeing to grasp that no amount of fretting will ever alter this truth. It’s still useful to make plans. But do that with the awareness that a plan is only ever a present-moment statement of intent, not a lasso thrown around the future to bring it under control. The spiritual teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti said his secret was simple: “I don’t mind what happens.” That needn’t mean not trying to make life better, for yourself or others. It just means not living each day anxiously braced to see if things work out as you hoped.

The solution to imposter syndrome is to see that you are one. When I first wrote about how useful it is to remember that everyone is totally just winging it, all the time, we hadn’t yet entered the current era of leaderly incompetence (Brexit, Trump, coronavirus). Now, it’s harder to ignore. But the lesson to be drawn isn’t that we’re doomed to chaos. It’s that you – unconfident, self-conscious, all-too-aware-of-your-flaws – potentially have as much to contribute to your field, or the world, as anyone else.

Humanity is divided into two: on the one hand, those who are improvising their way through life, patching solutions together and putting out fires as they go, but deluding themselves otherwise; and on the other, those doing exactly the same, except that they know it. It’s infinitely better to be the latter (although too much “assertiveness training” consists of techniques for turning yourself into the former).

Remember: the reason you can’t hear other people’s inner monologues of self-doubt isn’t that they don’t have them. It’s that you only have access to your own mind.

Selflessness is overrated. We respectable types, although women especially, are raised to think a life well spent means helping others – and plenty of self-help gurus stand ready to affirm that kindness, generosity and volunteering are the route to happiness. There’s truth here, but it generally gets tangled up with deep-seated issues of guilt and self-esteem. (Meanwhile, of course, the people who boast all day on Twitter about their charity work or political awareness aren’t being selfless at all; they are burnishing their egos.)

If you’re prone to thinking you should be helping more, that’s probably a sign that you could afford to direct more energy to your idiosyncratic ambitions and enthusiasms. As the Buddhist teacher Susan Piver observes, it’s radical, at least for some of us, to ask how we’d enjoy spending an hour or day of discretionary time. And the irony is that you don’t actually serve anyone else by suppressing your true passions anyway. More often than not, by doing your thing – as opposed to what you think you ought to be doing – you kindle a fire that helps keep the rest of us warm.

Know when to move on. And then, finally, there’s the one about knowing when something that’s meant a great deal to you – like writing this column – has reached its natural endpoint, and that the most creative choice would be to turn to what’s next. This is where you find me. Thank you for reading.

I'm not the only one who loves Oliver's work. Our guest in Chapter 28 of 3 Books, Mark Manson, said "Oliver Burkeman has a way of giving you the most unexpected productivity advice exactly when you need it" and our guest in Chapter 135, Cal Newport, said "More than a book of ideas, Meditations for Mortals offers a practical path toward personal transformation – one that helps you sidestep the shallow allure of frenetic busyness and find a liberating joy in the limits and imperfections of life. A must-read." Don't miss more of Oliver's potent wisdom in Chapter 142 of 3 Books.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

A few thoughts on gratitude...

Hey everyone,

Happy morning after the U.S. election.

I'm writing this before knowing who won and feeling slightly worried about the state of things.

But, you know, that's also where gratitude comes in. I've been writing about gratitude since I began my list of 1000 Awesome Things way back in 2008. I don't think I knew it so obviously then. Maybe it will help to start with a definition. I like what Robert Emmons (b. 1958), University of California gratitude researcher and author of 'The Little Book of Gratitude,' says:

Living gratefully begins with affirming the good and recognizing its sources. It is the understanding that life owes me nothing and all the good I have is a gift...

I like that! Let's start there. "All the good I have is a gift." If we start there then we pretty quickly can start feeling grateful ... for everything else. I'm lucky to be writing this. You're lucky to be reading it. We're lucky underground wires and flying satellites are letting us have this conversation. Lucky our eyeballs work! Lucky they can convert pixel streaks into thoughts! Never mind how lucky we both are to even have the time to chat like this.

Emmons calls gratitude "fertilizer of the mind" which helps to "spread connections and improve function in nearly every realm of experience." He said six years ago in 2018 in a "Science of Gratitude" paper that "Research suggests that gratitude inspires people to be more generous, kind, and helpful (or “prosocial”); strengthens relationships, including romantic relationships; and may improve the climate in workplaces." And even earlier than that, in 2013, on Daily Good he said that "grateful people are more resilient to stress, whether minor everyday hassles or major personal upheavals." This all makes sense! When we're focused on the positive the negative doesn't make as much of a mental clang.

Of course, my own attempts at gratitude are much smaller. Pithier! I started writing one "awesome thing" a day on June 20, 2008 and I ... never stopped. Over 150,000 people still read my new daily awesome thing (you can sign up here) and a few recent ones include "Getting late to hockey but making it on the ice in time," "When someone compliments your glasses," and "The smell of warm clothes when you open the dryer."

I'm a court jester next to the wise, sagacious Mary Oliver (1935-2019), though. I have posted poems of hers before like "Don't Hesitate" and "The Sun" and while writing this I came across "Messenger" which is a new fave:

My work is loving the world.

Here the sunflowers, there the hummingbird—

equal seekers of sweetness.

Here the quickening yeast; there the blue plums.

Here the clam deep in the speckled sand.Are my boots old? Is my coat torn?

Am I no longer young, and still half-perfect? Let me

keep my mind on what matters,

which is my work,which is mostly standing still and learning to be

astonished.

The phoebe, the delphinium.

The sheep in the pasture, and the pasture.

Which is mostly rejoicing, since all the ingredients are here,which is gratitude, to be given a mind and a heart

and these body-clothes,

a mouth with which to give shouts of joy

to the moth and the wren, to the sleepy dug-up clam,

telling them all, over and over, how it is

that we live forever.

To close off I dug up a book called, fittingly, 'Gratitude' by Oliver Sachs (1933-2015), the British neurologist and naturalist perhaps most famous for writing the book that became the movie Awakenings.

I like this quote:

There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate—the genetic and neural fate—of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death. I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers. Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.

I love that. "An intercourse with the world." Maybe that's what gratitude is ... just having that (uh) daily world intercourse. Where you see the bugs and the flowers and the birds and the trees and the smiles and the sunsets and, well, all of it, as a wondrous gift.

Can we live in that mindset all the time? No! Of course not. But that's why we have these conversations—these re-visitings—to just help keep steering ourselves slowly back to awe.

We are very grateful to be here. I am grateful for your love and energy along the way.

Thanks, as always, for being here. And you can invite others into our community here.

Neil

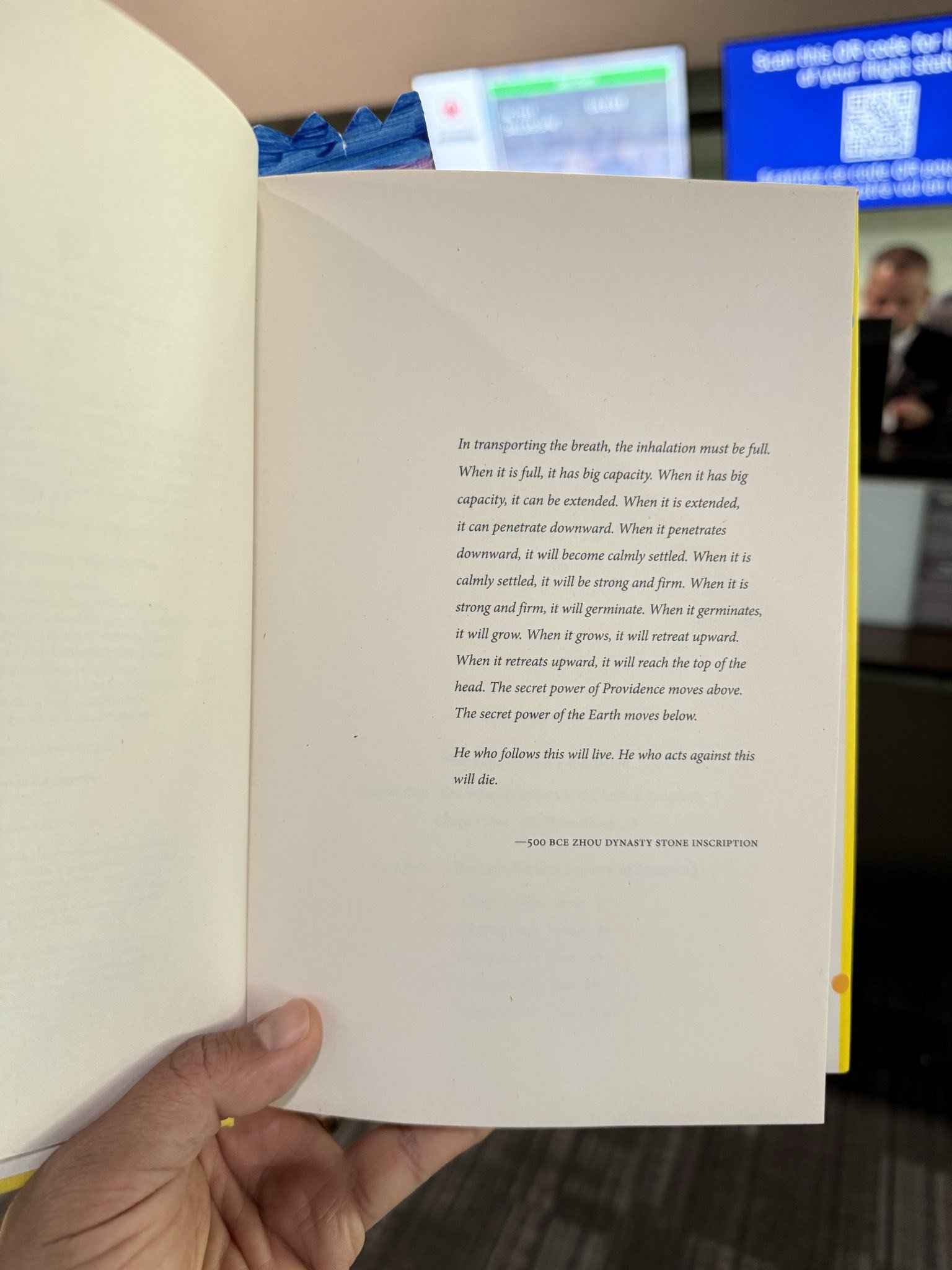

Take a deep breath - Excerpt from from 'Breath' by James Nestor

Hey everyone,

I suddenly can't shut up about the book 'Breath' by James Nestor. I have so many dog-eared pages, so many highlights. Basically I've realized that me and maybe half of us are breathing completely wrong. I'll share my full review on Saturday, but for now I wanted to leave you with the book's Epigraph which is from a 2500-year-old stone inscription in China.

Take a deep breath, read it slowly, and ask yourself if you feel you can breathe better. Check out the book here and make sure you're on my book club mailing list here.

Neil

In transporting the breath, the inhalation must be full. When it is full, it has big capacity. When it has big capacity, it can be extended. When it is extended, it can penetrate downward. When it penetrates downward, it will be come calmly settled. When it is calmly settled, it will be strong and firm. When it is strong and firm, it will germinate. When it germinates, it will grow. When it grows, it will retreat upward. When it retreats upward, it will reach the top of the head. The secret power of Providence moves above. The secret power of the Earth moves below. He who follows this will live. He who acts against this will die.

—500 BCE Zhou Dynasty stone inscription

Want to harness your breathe to help you meditate but afraid of doing it wrong? Learn the three biggest myths about meditation here.

Did you know that trees release phytoncides, chemicals that can reduce adrenaline and cortisol in your body? Practice your deep breathing and take a walk in nature.

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

More birthday wisdom from readers...

I started publishing a list of advice on my birthday. I did it when I turned 43, 44, and last week when I turned 45. The post last week went wildly viral with over 400,000 people reading it. And now, most excitingly, I'm seeing so many others writing and sharing their own lists back.

"I'm a Mum of 3 awesome kids and call Sydney, Australia home," Ness Quayle wrote to me last week. "When I was 9, I tragically lost my father. He was 42 years young. A few days ago, I turned 42 and my daughter, Ella, is 9. The significance of these ages has stirred a number of emotions in me for a number of months. What if I were to pass away? What would my kids remember of their Mother or me as a woman?"

I relate to this feeling. Not fear exactly but—the human desire to etch ourselves into the stone a little bit? To feel like carving coherence in the blur of inchoate motion. Ness continues: "Writing this list was cathartic, as I desire to share with my kids my ideas, thoughts, and values. To preserve my voice in some small way, just in case, so they can refer to it at any time throughout their life. I highly recommend everyone giving this a red hot go!"

So do I! And now, without further ado, here are wonderful lists of birthday advice from Ness, Meredith, Christine, Michelle, and Sera.

Neil

P.S. Do you have a list of advice inside you? Please reply and share it with me or, as Ness says, give it a red hot go!

42 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 42

Written by Ness Quayle

1. You’re never fully dressed without a smile or eyeliner.

2. Don’t water a garden you don’t want to grow.

3. Marmalade and vegemite on toast. It’s salty, sweet deliciousness.

4. Pay attention to what you pay attention to.

5. “Talk less, smile more” (Hamilton) when dealing with narcissists.

6. Ask for help from your mates and spiritual guides, they’ll always step up.

7. Call over text. It means a lot.

8. Keep going.

9. Prioritising my nervous system response has changed my dating life.

10. Sleepovers with besties are magic.

11. Farting in front of my kids is hilarious.

2. Build muscle. It won’t make you bulky.

13. Laughter, sunlight, and 2 minute dance breaks are medicine for the soul.

14. Take photos and then put away the phone.

15. Always bring food to school pickups.

16. Slowing down each inhale and exhale immediately changes your state.

17. Start with the end in mind but don’t be too attached to the outcome. (It’s who you become on the journey that matters.)

18. Talk to strangers; they’re genuinely very receptive and kind.

19. Inner child work is essential work.

20. Experiences over things. Actions over words.

21. Never leave home without a water bottle.

22. There’s no such thing as one-way liberation.

23. Friends can help heal a heart they didn’t break.

24. Per aspera ad astra…Through adversity to the stars ✨

25. Always commit to a Fancy Dress party. The joy of dressing up is contagious.

26. Record your kids voices, laughter, and opinions. It’s glorious looking back.

27. Afternoon naps and spicy margaritas are heaven-sent.

28. Slowing down gets you there faster, and in better shape.

29. Genuine curiosity is so damn attractive.

30. Cut multiple keys to your front door and remember where you’ve hidden them.

31. Use the line “by the end of this chat, I hope there’s greater understanding between us” before starting a difficult conversation.

32. I firmly identify as Ness. Not Vanessa.

33. Attend live events. A collective, shared human experience is so powerful.

34. Playing handball regularly with my kids has been game-changing for our relationship.

35. Travel solo.

36. If you can’t find time to meditate for 5 minutes, you need 10.

37. Demonstrate to your kids what relaxation and a wholehearted apology looks like.

38. One day, this will all make sense.

39. Watching Graham Norton on YouTube always improves my mood. 40. You are not your thoughts. You are the observer of your thoughts. 41. Sunrise is the best part of the day.

42. “Keep peace in your soul. With all its sham, drudgery and broken dreams, it is still a beautiful world. Be cheerful. Strive to be happy.” (Max Ehrmann)

3o Things I’ve (Almost) Learned As I Turn 30

Written by Sera Ertan

1. Dream bigger than what you think is possible.

2. Have that slice of cake and glass of wine.

3. Always find a reason to celebrate life.

4. If you think you can pull it off, wear it.

5. Explore dating outside of your type.

6. To stretch time and add years to your life, go somewhere you have never been.

7. Let strangers become friends and genuinely listen to their stories, you will be surprised by how much anyone can teach you.

8. Sun and sea might be enough to cure your depression.

9. If you are unhappy, move, you are not a tree.

10. Everything has a solution when you allow yourself to think outside the box.

11. Express your emotions, life is too short not to tell people to fuck off.

12. Stop caring about what others will think about you, nobody is thinking about you.

13. Let your intuition guide you, or you will resent the life you live.

14. Do not overcomplicate life.

15. There is always more to learn, be open to new knowledge and accept the fact that you know very little.

16. Experiment and choose the diet that works best for your body, don’t let vegans (or anyone extreme for that matter), convince you otherwise.

17. Weight all opinions, but make your own decision.

18. Take the risk, and watch life support you.

19. Do more of what brings you peace.

20. Create your own workout regimen and stick to it.

21. Don’t get bogged down by the past and the future, stay in touch with the present moment.

22. Focus only on your very next step.

23. Learn a new skill every year.

24. Remember that you are free to recreate yourself and become a completely new person any moment you want.

25.Be fully yourself around people and let whoever wants to leave leave.

26. Call your mom and dad more often.

27. Where you are is where you are meant to be.

28.You set your own limits.

29. Stay curious and embrace change.

30. Enjoy the ride.

60 Life Lessons Learned In 60 Years

Written by Michelle Oram

1. Don’t put a wool sweater in the washing machine if you ever want to wear it again.

2. You can take a 2-week trip with just a carry-on.

3. Drying laundry outdoors saves money, makes your clothes last longer—and they will smell oh so good!

4. Homemade soup is the best comfort food.

5. Don’t postpone happiness. Enjoy today because tomorrow isn’t guaranteed.

6. Avoid depending on other people to make you happy. True happiness comes from within.

7. Find things to love about yourself. If you’re not happy with yourself, you’re not ready for a relationship.

8. Being a mom is hard sometimes, but it’s so worth it.

9. When your kids grow up and leave home, you’ve done your job of raising them to be independent adults.

10. Our family stories matter so we need to share them.

11. True friendships stand the test of time and distance.

12. If there’s something you want to do, just do it. That way you’ll never have to ask, “What if?”

13. The real learning starts after you leave school.

14. There’s always something new to learn, and you’re never too old to learn it.

15. Don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t do anything. Tune out the naysayers.

16. Do your homework and form your own opinions.

17. Be satisfied with progress instead of seeking perfection.

18. Choose your own success criteria rather than measuring your success by the standards or actions of others.

19. Don’t buy more house than you need. In fact, don’t buy more of anything than you need.

20. Always set some money aside for emergenceis because rainy days will come.

21. Get into the habit of saving early in life and save as much as you can.

22. Pay off debt as quickly as possible.

23. Health will always be more important than money.

24. Trust your instincts when if comes to your health. If something doesn’t feel right, look into it.

25. How you feel matters more than how you look.

26. You don’t need to be an athlete, or even have athletic ability, to live an active lifestyle. There’s a lesson I wish I’d learned before high school gym class.

27. Exercise gives you energy.

28. Getting outdoors every day boosts your mood and increases creativity. And it makes winter bearable.

29. Material possessions aren’t the key to happiness. You can be happy with very little.

30. Quality over quantity in all things.

31. Take time to appreciate the simple, everyday pleasures.

32. Appreciate what you already own rather than yearning for the next thing.

33. Don’t get sucked into FOMO. There will always be someone with bigger, better, or more things than you have.

34. A handwritten note will make your day…or someone else’s.

35. You don’t really need the latest and greatest of anything.

36. Schedule downtime in your calendar.

37. Your age doesn’t define you.

41. Be grateful for the privilege of growing older.

42. Choosing to age gracefully is liberating.

43. Laughter really is the best medicine.

44. It doesn’t matter what other people think of you.

45. Don’t get sucked into negativity.

46. Kindness costs nothing.

47. Be authentic.

48. Music makes everything better.

49. Strong faith makes life’s troubles easier.

50. You can count on your faith community in difficult times.

51. Volunteer. You’ll get back more than you give.

52. Giving to others feels good.

53. The people you work with and the relationships you form matter as much as the work you do.

54. It’s okay to change direction and choose a different career path.

55. Your career is just one aspect of your life. Keep it in perspective.

56. Fully disconnect during your vacation time. No matter your role, work will survive without you.

57. Retirement is a beginning, not an end.

58. Make time to do things that make you happy.

59. If something matters enough to you, you’ll find time for it.

60. Finally, the years will fly by. I don’t quite believe I’m turning 60 and often wonder where the years have gone. In my head I’m still 18. That’s why it’s important to enjoy every day and not take life for granted.

46 Things I’ve (Almost) Learned As I Turn 46

Written by Christine Da Silva

1. My happiness is my responsibility.

2. Take care of your health before it becomes your mental illness.

3. No response is a powerful response.

4. Sometimes things don’t get easier, you just get stronger.

5. Always listen to your intuition, even if it scares you.

6. Teachers don’t know everything. Mine told me spelling was important and that I’d never carry a calculator in my pocket.

7. Expect nothing and you will never be disappointed.

8. Being a mom is only a small part of who I am.

9. Actions need to match effort.

10. Some people come into your life when you need them, they don’t always need to stay.

11. I am, always have been and always will be enough.

12. My deepest wounds did not come from my enemies.

13. You are never too old.

14. It is never too late.

15. Peanut butter cups taste way better frozen.

16. Real queens fix each others’ crowns.

17. When you see something, you like in someone tell them.

18. I don’t have time is a bullshit excuse.

19. A Stop Doing list is just as important as a To Do list.

20. Music is so much better at full blast with the windows down.

21. My alone time is for your safety.

22. I survived all the days I thought I wouldn’t.

23. Pictures will become more important, get in them.

24. Some people don’t deserve an explanation.

25. No one is making it out of here alive.

26. I would rather have your time then your money.

27. “No” is a complete sentence.

28. Just one more page/chapter is the biggest lie I tell myself most often.

29. Your opinion of me is none of my business.

30. The glass isn’t half full or half empty, its refillable.

31. If they want to they will.

32. Always choose happiness over history.

33. I am not my thoughts; I am the watcher of them.

34. Lessons repeat themselves until you learn them.

35. There is always light after darkness.

36. My children have taught me more than anyone else.

37. The universe will whisper to you until she needs to scream to get your attention.

38. The secret to happiness is to always have a vacation booked.

39. My boundaries only bother those who don’t respect me.

40. Theres always 3 sides to every story, your side, their side, and the truth…or the screenshots.

41. Somethings are not worth the jail time.

42. Getting older is better than the alternative.

43. What you allow will continue.

44. I am forever learning.

45. Nothing changes if nothing changes.

46. Eat the damn cake!

48 Things I Learned As I Turned 48

Written by Meredith Foxx

1. You’re never fully dressed without lipstick (or for that matter blush).

2. Sleep is underrated.

3. It’s okay to say NO.

4. Teach yourself to stop ruminating.

5. The “wait 24 hours before sending an email” works.

6. No need to photograph everything.

7. You can break a bad habit (i.e. diet coke)

8. Better to be overdressed than underdressed.

9. Know your city officials.

10. Know your neighbors.

11. Don’t be afraid to ask people questions about themselves.

12. Listen to songs that remind you of your past & good times you have had. (Neil Diamond-

High School).

13. It’s okay to be a tourist in a new city- explore.

14. Accept compliments & criticism.

15. Have a actual key to your house.

16. Learn Brevity.

17. Get up and move/walk during a workday (preferably outside).

18. Stop overbuying groceries- wasteful.

19. Try clothes on before you buy them.

20. All couples should have to put a piece of furniture together- you learn a lot.

21. Reading is true joy.

22. Recognizing others for their accomplishments is underrated.

23. Stop using the word “just”.

24. If you don’t like the book- stop reading it.

25. Handwritten thank you notes & sympathy cards are meaningful- take the time.

26. Stop wishing time away.

27. If you don’t want to go- don’t go.

28. If you don’t like the product, throw it out (skin, hair, makeup). It’s a sunk cost.

29. Priorities change-that is okay.

30. Not all stress is bad.

31. Have a will.

32. Just like sending an email-wait 24 hours before purchasing everything in your “online”

cart.

33. Throw away clothes that are worn.

34. Hungry and being temperature hot is a bad combination.

35. Petting your dogs (or pets) always will make you happy.

36. Don’t be afraid of preventative health screenings-get them done.

37. Rewatch your favorite movies as a kid (For me: Sound of Music & The Wizard of Oz)

38. Don’t wait to use stuff- use it.

39. You don’t have to clean your plate.

40. Always pack a toothbrush, toothpaste, tissues, spare undergarments and socks in your

carry on.

41. Keep traditions and make new ones.

42. Learn when to be quiet.

43. Don’t let your low fuel light come on in the car.

44. Get a car wash.

45. Be humble.

46. Be kind.

47. Be patient.

48. Be forgiving

And for 45-48- of others and yourself.

Read more of my birthday advice...

45 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 45

44 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 44

43 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 43

...And then write your own and share with me!

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

45 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 45

Hey everyone,

Today is my birthday! And with it comes my usual dose of completely unrequested advice. As always, take what works, ditch what doesn't! And if you'd like to read the first two editions of this series here is my "43 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 43" and "44 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 44."

Let me know which ones you like, didn't like, or any suggestions for next year!

Neil

45 Things I've (Almost) Learned As I Turn 45

1. Slice the bagels before you freeze them.

2. Every time you’re talking about someone pretend they’re standing right behind you.

3. If you don’t love the pants at the store you’ll hate them at home.

4. Before you move in together: travel.

5. Motivation does not cause action. Action causes motivation.

6. If you’re talking on the phone and you’re on the toilet—flush later.

7. Airport Rule: Farther the walk cleaner the bathrooms.

8. What costs nothing but is exceedingly rare and valuable? Eye contact.

9. Money does buy happiness if you buy 1 of 3 S’s: Social (going out with friends), Sweat (joining a team), Skill (taking a class).

10. Wait a day before replying to an email that makes you angry. (You can always tell them to go to hell tomorrow.)

11. Never take something you've never taken before doing something you've never done.

12. Best and bestseller are not the same thing.

13. Relationship Tip: Find someone who laughs at your jokes and someone whose jokes you laugh at.

14. Many people wish they had one more kid. Few people wish they had one less kid.

5. “No” is a complete sentence.

16. “I failed med school” is fact, “I failed my parents” is story, “I’m addicted to booze” is fact, “I’ve ruined my life” is story, “I’m going bald” is fact, “I’ll never get married” is story. For better self-talk peel stories off facts.

17. In an era of endless choice the value of curation skyrockets.

18. Before renovating: Mentally double the price and double the time. Then, if you’d still do it, do it.

19. Fat doesn’t make you fat. Sugar makes you fat.

20. When investing with friends assume it's gone.

21. At holiday meals: Let the family member with the youngest child choose the dinner time.

22. Pay attention to what you pay attention to.

23. Public speaking tip: If you want praise, ask the audience. If you want feedback, ask the AV guy.

24. Good line during fights: “The story I’m telling myself is…”

25. Online everyone is beautiful and it’s ugly. Offline everyone is ugly and it’s beautiful.

26. Ladder-climbing tip: “What interests my boss fascinates me.”

27. Social media wants us to spend money we don’t have on things we don’t need to create perceptions that don’t last from people we don’t know.