How To Have More (And Better!) Vacation

I researched broken vacation policies.

The solution is not what you think.

Hey everyone,

I thought as we get close to 'summer vacation' time I'd share an article I wrote with Shashank Nigam for Harvard Business Review about the idea of 'forced' vacation time. Has the idea caught on? No! Not at all! And yet: I keep thinking it has legs. It certainly worked at this small business. Take a read and I'd love to hear what your organization does to make vacation really work...

Neil

What One Company Learned from Forcing Employees to Use Their Vacation Time

Written by Neil Pasricha & Shashank Nigam

Have you ever felt burned out at work after a vacation? I’m not talking about being exhausted from fighting with your family at Walt Disney World all week. I’m talking about how you knew, the whole time walking around Epcot, that a world of work was waiting for you upon your return.

Our vacation systems are completely broken. They don’t work.

The classic corporate vacation system goes something like this: You get a set number of vacation days a year (often only two to three weeks), you fill out some 1996-era form to apply for time off, you get your boss’s signature, and then you file it with a team assistant or log it in some terrible database. It’s an administrative headache. Then most people have to frantically cram extra work into the week(s) before they leave for vacation in order to actually extract themselves from the office. By the time we finally turn on our out-of-office messages, we’re beyond stressed, and we know that we’ll have an even bigger pile of work waiting for us when we return. What a nightmare.

For most of us, it’s hard to actually use vacation time to recharge. So it’s no wonder that absenteeism remains a massive problem for most companies, with payrolls dotted with sick leaves, disability leaves, and stress leaves. In the UK, the Department for Work and Pensions says that absenteeism costs the country’s economy more than £100 billion per year. A white paper published by the Workforce Institute and produced by Circadian, a workforce solutions company, calls absenteeism a bottom-line killer that costs employers $3,600 per hourly employee and $2,650 per salaried employee per year. It doesn’t help that, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the United States is the only country out of 21 wealthy countries that doesn’t require employers to offer paid vacation time. (Check out this world map on Wikipedia to see where your country stacks up.)

Would it help if we got more paid vacation? Not necessarily. According to a study from the U.S. Travel Association and GfK, a market research firm, just over 40% of Americans plan not to use all their paid time off anyway.

So what’s the progressive approach? Is it the Adobe, Netflix, or Twitter policies that say take as much vacation as you want, whenever you want it? Open-ended, unlimited vacation sounds great on paper, doesn’t it? Very progressive, right? No, that approach is broken too.

What happens in practice with unlimited vacation time? Warrior mentality. Peer pressure. Social signals that say you’re a slacker if you’re not in the office. Mathias Meyer, the CEO of German tech company Travis CI, wrote a blog post about his company abandoning its unlimited vacation policy: “When people are uncertain about how many days it’s okay to take off, you’ll see curious things happen. People will hesitate to take a vacation as they don’t want to seem like that person who’s taking the most vacation days. It’s a race to the bottom instead of a race towards a well rested and happy team.”

The point is that in unlimited vacation time systems, you probably won’t actually take a few weeks to travel through South America after your wedding, because there’s too much social pressure against going away for so long. Work objectives, goals, and deadlines are demanding. You look at your peers and see that nobody is backpacking through China this summer, so you don’t go either. You don’t want to let your team down, so your dream of visiting Machu Picchu sits on the shelf forever.

What’s the solution?

Recurring, scheduled mandatory vacation.

Yes, that’s right — an entirely new approach to managing vacation. And one that preliminary research shows works much more effectively.

Designer Stefan Sagmeister said in his TED talk, “The Power of Time Off,” that every seven years he takes one year off. “In that year,” he said, “we are not available for any of our clients. We are totally closed. And as you can imagine, it is a lovely and very energetic time.” He does warn that the sabbaticals take a lot of planning, and that you get the most benefit from them after you’ve worked for a significant amount of time.

Why does he do this? He says, “Right now we spend about the first 25 years of our lives learning, then there are another 40 years that are really reserved for working. And then tacked on at the end of it are about 15 years for retirement. And I thought it might be helpful to basically cut off five of those retirement years and intersperse them in between those working years.” As he says, that one year is the source of his creativity, inspiration, and ideas for the next seven years.

I recently collaborated with Shashank Nigam, the CEO of SimpliFlying, a global aviation strategy firm of about 10 people, to ask a simple question: “What if we force people to take a scheduled week off every seven weeks?”

The idea was that this would be a microcosm of the Sagmeister principle of one week off every seven weeks. And it was entirely mandatory. In fact, we designed it so that if you contacted the office while you were on vacation — whether through email, WhatsApp, Slack, or anything else — you didn’t get paid for that vacation week. We tried to build in a financial punishment for working when you aren’t supposed to be working, in order to establish a norm about disconnecting from the office.

The system is designed so that you don’t get a say in when you go. Some may say that’s a downside, but for this experiment, we believed that putting a structure in place would be a significant benefit. The team and clients would know well ahead of time when someone would be taking a week off. And the point is you actually go. And everybody goes. So there are no questions, paperwork, or guilt involved with not being at the office.

After this experiment was in place for 12 weeks, we had managers rate employee productivity, creativity, and happiness levels before and after the mandatory time off. (We used a five-point Likert scale, using simple statements such as “Ravi is demonstrating creativity in his work,” with the options ranging from one, Strongly Disagree, to five, Strongly Agree.) And what did we find out?

Creativity went up 33%, happiness levels rose 25%, and productivity increased 13%. It’s a small sample, sure, but there’s a meaningful story here. When we dive deeper on creativity, the average employee score was 3.0 before time off and 4.0 after time off. For happiness, the average employee score was 3.2 before time off and 4.0 afterward. And for productivity, the average employee score was 3.2 before and rose to 3.6.

This complements the feedback we got from employees who, upon their return, wrote blog posts about their experiences with the process and what they did with their time. Many talked about how people finally found time to cross things off of their bucket lists — finally holding an art exhibition, learning a new language, or traveling somewhere they’d never been before.

Now, this is a small company, and we haven’t tested the results in a large organization. But the question is: Could something this simple work in your workplace?

There were two points of constructive feedback that came back from the test:

Frequency was too high. Employees found that once every seven weeks (while beautiful on paper) was just too frequent for a small company like SimpliFlying. Its competitive advantage is agility, and having staff take time off too often upset the work rhythm. Nigam proposed adjusting it to every 12 weeks. But with employee input, we redesigned it to once every eight weeks.

Staggering was important. Let’s say that two or three people work together on a project team. We found that it didn’t make sense for these people to take time off back-to-back. Batons get dropped if there are consecutive absences. We revised the arrangement so that no one can take a week off right after someone has just come back from one. The high-level design is important and needs to work for the business.

This is early research, but it confirms something we said at the beginning: Vacation systems are broken and aren’t actually doing what they’re advertised to do. If you show up drained after your vacation, that means you didn’t get the benefit of creating space.

Why is creating space so important?

Consider this quote from Tim Kreider, who wrote “The ‘Busy’ Trap” for the New York Times:

Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice; it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets. The space and quiet that idleness provides is a necessary condition for standing back from life and seeing it whole, for making unexpected connections and waiting for the wild summer lightning strikes of inspiration — it is, paradoxically, necessary to getting any work done.

Fix your vacation system. You’ll be doing better, more important work.

Contrary to popular discourse, we actually do like to work...

...But that doesn't mean you're in the right job to feel fulfilled—even if it has a great vacation policy!

Sign Up for a Dose of Inspiration:

Every other week, I send an email out with an article I’ve written, or one of my favorite speeches, essays, or poems. No ads, no sponsors, no spam, and nothing for sale. Just a dose of inspiration or beauty!

Want to beat the algorithm? Don't play the game

How often are you too busy?

Like the fizz is bubbling over the lip of your cup?

Me, honestly, more often than I’d like. I think of myself as a writer. You know: urban flâneuring between coffee shops where I drip out paragraphs of poignancy for my next book.

But, in reality: I got deadlines! At least once or twice a week I look at my to-do list and a little fireball of stress bubbles up inside. Podcasts need editing, posts need writing, slides need building, and, you know, sure: I have some good systems—Parkinson's Law! Untouchable Days! Productivity tips up the wazoo!—but the truth is there’s some bigger issue culturally and I find it helpful to stay aware of it.

A dozen years ago Tim Kreider called the problem the ‘busy’ trap, pointing out that people telling you how busy they are has "become the default response when you ask anyone how they’re doing."

As Tim writes:

Even children are busy now, scheduled down to the half-hour with classes and extracurricular activities. They come home at the end of the day as tired as grown-ups. I was a member of the latchkey generation and had three hours of totally unstructured, largely unsupervised time every afternoon, time I used to do everything from surfing the World Book Encyclopedia to making animated films to getting together with friends in the woods to chuck dirt clods directly into one another’s eyes, all of which provided me with important skills and insights that remain valuable to this day. Those free hours became the model for how I wanted to live the rest of my life.

And this was in 2012 before the Internet bullet train accelerated into the everything-blurry-out-the-window mode we're cruising at now.

Tim called this busyness out and said we’re feeling too anxious or guilty when we aren’t working. I know I was definitely busy in 2012—I had gone through a divorce and was living in a tiny downtown condo while working as chief of staff for Dave Cheesewright by day, writing 1000 Awesome Things every night, and stuffing in writing of three books and a couple page-a-day calendars while also giving talks every weekend. I felt beyond busy—more dead-man-walking, really, getting 3-4 hours of sleep a night, and coming to epitomize the definition of burnout.

Another person I have found helpful on my journey since then is Douglas Rushkoff. Back in 2012, in my high-burnout years, he was named by MIT Technology Review the 6th most influential thinker in the world (behind heavyweights like Daniel Kahneman and Steven Pinker) although I didn't personally find him until I read his 'Team Human' a few years later. That book sang to my soul and I put it in one of my Very Best Books lists.

I’ve since followed everything Douglas. I started listening to his biweekly Team Human podcast and he was kind enough to blow our minds on 3 Books where his distillation of 'Go, Dog! Go' by P. D. Eastman may be the best children’s book analysis I’ve heard. He then increased the publishing schedule of Team Human and he started up a new Substack newsletter. At age 63, after dozens of books and documentaries, while working full-time as a professor, it seemed he was accelerating into Peak Douglas!

But then he came back to his team human roots and on May 3, 2024 he published a wonderful piece called 'Breaking from the Pace of the Net' with the opening line "I can’t do this anymore."

He goes on to explain:

Oh, I’m happy to write and podcast and teach and talk. That’s me, and that’s all good. What I’m finding difficult, even counter-productive, is to try to keep doing this work at the pace of the Internet.

Podcasting is great fun, and if it were lucrative enough I could probably record and release one or two episodes a week without breaking too much of a sweat. That’s the pace encouraged by both the advertising algorithms and the patronage platforms. Advertisers can more easily bid for spots on a show with a predictable schedule on specified days. Likewise, paying subscribers have come to expect regular content from the podcasts they support. Or at least the platforms encourage a regular rhythm, and embed subtle cues for consistency.

Substack, while great for a lot of things, is even worse as far as its implied demand for near-daily output. If I really wanted to live off a Substack writing career, I would have to ramp up to at least three posts a week. That might work if I were a beat reporter covering sports, but - really - how many cogent ideas about media, society, technology and change can one person develop over the course of a week? More important, how many ideas can one person come up with that are truly worth other people’s time?

I relate deeply to this feeling. The thirsty more-ness the Internet demands! When I launched 3 Books in 2018 it zoomed up the Apple rankings and became one of the Top 100 shows in the world. My podcast friends started texting me "Release your show weekly! Daily! You’ll stay on top!" But I was committed to my lunar-based schedule—I knew I needed time to properly prepare and go deep on each chat—and, of course, the algorithms punished me for that. If others are posting weekly, or daily, or multiple-times-a-day, they will be rewarded for increasing eyeballs and ears on the platform and, unless you keep up, you’ll slowly slip away.

Back to Douglas:

… while I love being able to engage with readers and listeners and Discord members through many modes, I am coming to realize my sense of guilty obligation to all the people on all these platforms is actually misplaced. The platforms themselves are configured to tug on those triggers of responsibility, the same way Snapchat uses the “streak” feature to keep tween girls messaging each other every day. They’re not messaging out of social obligation, but to keep the platform’s metric rising. It’s early training for the way their eventual economic precarity will keep them checking for how much money a Medium post earned, or how many new subscribers were generated by a Substack post.

Most ironically, perhaps, the more content we churn out for all of these platforms, the less valuable all of our content becomes. There’s simply too much stuff. The problem isn’t information overload so much as “perspective abundance.” We may need to redefine “discipline” from the ability to write and publish something every day to the ability hold back. What if people started to produce content when they had actually something to say, rather than coming up with something to say in order to fill another slot?

I love that.

What if people started to produce content when they had actually something to say? It almost sounds so laughably arcane. This is the uncle of yours who posts on Instagram three times a year. But they’re of his birthday, the family reunion, and the time he was in Whistler and saw a Steller’s Jay. It’s the globe-trotting friend who sends a long email once a month—but they’re good, and juicy, and you feel like you’re there. Less is more!

Isn’t this exactly what Cal Newport’s been preaching in his new book 'Slow Productivity' where he encourages us to 1) do fewer things, 2) work at a natural pace, and 3) obsess over quality? Not easy when the Internet rewards doing more things, working at an unnatural pace, and obsessing over quantity.

Cal says the benefits that technology have accrued have also created the ability to stack more into our days than we can possibly handle. He points out that we’re overworked, overstressed, constantly dissatisfied, and trying to hit a bar that feels like it’s always moving up. One reason his book has struck a chord is because, in his words:

This lesson, that doing less can enable better results, defies our contemporary bias toward activity, based on the belief that doing more keeps our options open and generates more opportunities for reward.

Why? Because:

We've become so used to the idea that the only reward for getting better is moving toward higher income and increased responsibilities that we forget that the fruits of pursuing quality can also be harvested in the form of a more sustainable lifestyle.

A more sustainable lifestyle! That sounds good, doesn’t it? I think for me it’s worth checking in with myself to ensure I’m ‘working at a natural pace,’ which, thankfully, I seem to be getting better at than my grinding-till-4am-in-my-shoebox-condo days. And I need to keep relying on truth-tellers, like Tim, Douglas, and Cal here, to help me resonate with something I know deeply but, of course, often forget: life isn’t measured in outputs. It’s measured in love, in connection, in trust, in kindness, in passions, in memories. There are so many invisible but much-more-important guideposts when we look back on our lives from the end of it.

I like how Douglas ended his post with a thoughtful re-balancing act and a public commitment to realignment:

What I value most and, hopefully, offer is an alternative to the pacing and values of digital industrialism. That’s what I’m here for: to express and even model a human approach to living in a digital media environment. So I’m getting off the treadmill, recognizing this assembly line for what it is, and trusting that you will stay with me on this journey in recognition of the fact that less is more.

I’ll stay with you on your journey, Douglas. I like your style! And shall we revisit Tim Kreider, too? Near the end of 'The Busy Trap' he shares a note from a friend who left the rat race in the big city to live abroad:

The present hysteria is not a necessary or inevitable condition of life; it’s something we’ve chosen, if only by our acquiescence to it. Not long ago I Skyped with a friend who was driven out of the city by high rent and now has an artist’s residency in a small town in the south of France. She described herself as happy and relaxed for the first time in years. She still gets her work done, but it doesn’t consume her entire day and brain. She says it feels like college—she has a big circle of friends who all go out to the cafe together every night. She has a boyfriend again. (She once ruefully summarized dating in New York: “Everyone’s too busy and everyone thinks they can do better.”) What she had mistakenly assumed was her personality—driven, cranky, anxious and sad—turned out to be a deformative effect of her environment.

Let’s be wary of our environment. Our culture! How it’s forming, shaping, and styling itself around us, and how we may be bending, tilting, wilting against our natural preferences in ever-so-slight ways that we don’t always notice.

This post is a reminder, to myself, and maybe a few others, to keep checking in, valuing the big things, and steering ourselves towards space, time, and quality—while staying aware and resisting the pressures to do the opposite.

I’ll close with a short poem called 'Leisure' that I keep coming back to. It was written 113 years ago by Welsh poet W. H. Davies and it’s ever-so-simple but carries a reminder I like to tuck in my pocket whenever I find myself wondering whether or not to hit the gas.

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.No time to stand beneath the boughs

And stare as long as sheep or cows.No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass.No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night.No time to turn at Beauty's glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance.No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began.A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

I hope you find some time to stand and stare today.

—Neil

Want some inspiration to stop and stare? Listen to my 3 Books conversation on breaking boundaries to become better birdwatchers with J. Drew Lanham.

Can't put down your phone long enough to find a bird? Or feel like you have to turn that bird into content for the social media hype train? Here are 6 ways to reduce cell phone addiction.

Get my biweekly Neil.blog newsletter direct to your inbox:

How to Embrace the Most Embarrassing Parts of Your Resume

Everyone’s resume has a dud or two. Glaring gaps after getting fired. That new boss who reorganized your team–and maybe didn’t like you that much–and gave you a title demotion you’re still embarrassed about. And let’s not forget your short-lived stint as VP of operations at a hypergrowth startup, where your chief responsibility was packing boxes til midnight on Fridays until your partner cried foul.

I feel uncomfortable about parts of my career history, too. I went headfirst into marketing after college before realizing it was an Excel job and I expected a Powerpoint one. I started a restaurant that flopped. I made lateral moves, playing hot potato with my career for about a decade without ever cracking the ranks of leadership.

But what if duds like these aren’t duds? What if they’re simply the points on the zigzagging line that leads to the presently crystallized version of you? Someone with experience, know-how, and the crucial leadership traits of humility and empathy gleaned from working in the battlefields and the trenches–not just commanding the fleets?

Or hey, maybe not. Even so, the ability to take command of your resume–whatever it looks like–and tell a compelling narrative about your career couldn’t be more critical. Selling your experience is a vital skill, whether you’re on a job interview or wooing clients for your solo business. But to do that well, you first need to come to grips with the parts of your job history that you’re least interested in talking about. And that means working your way through these three phases:

Hide

Apologize

Accept

Here’s what that looks like.

PHASE 1: HIDING

For years I was embarrassed that I worked at Walmart. At parties or industry events, I answered the question the same way many of my coworkers did.

Them: So where do you work, anyway?

Me: Retail.

Them: Cool.

Eventually, I started to realize that masking is a form of self-judgment. I wasn’t confident about working at Walmart. I was afraid to mention the company because I was afraid of people’s perceptions: Main-Street-obliterating, fair-wage–damaging, soul-destroying behemoth corrupting society.

By acting awkwardly, I made things awkward for others.

That may not have been true, but whatever they were going to think, I wanted to avoid confronting it. Rather than acknowledge this part of my identity, I hid it. I didn’t mention it in my biography, my blog, any of my books, radio lead-ins, or newspaper interviews.

And I called this humility. But it was really fear. After a few years, I finally figured this out and decided that from then on, I would tell anybody exactly where I worked if they asked. Of course, I did this in a tentative, awkward way.

PHASE 2: APOLOGIZING

It went something like this:

Them: So where do you work, anyway?

Me: (grimacing) Uh . . . Walmart?

Them: Oh, uh, okay, haha . . . yeah, I heard of the place! Haha, uh . . .

By acting awkwardly, I made things awkward for others. By apologizing for myself, I forced others to apologize, too. Eventually, I realized that apologizing was a form of self-judgment in the way that hiding my job history was.

Arguably, it even made things worse. I was communicating a part of myself, then immediately sounding a Family Feud–style buzzer after my own response:

“We surveyed 100 people and the top five answers are on the board. Name a place you have worked.”

“Uh . . . Walmart?”

NNNNNNN!

Apologizing avoids ownership. It creates distance. It suggests a mistake–one that you then need to account for. Apologizing is what you do when your dog craps on the neighbor’s lawn and then you notice your neighbor watching from the window. (Sorry, Keith!)

Do this kind of thing on a job interview, even unwittingly, and a hiring manager will notice immediately. Eventually I clued in to this bad habit myself, and after a couple years of apologizing for my own resume, I finally moved on to the third and final step.

PHASE 3: ACCEPTANCE

Them: So where do you work, anyway?

Me: Walmart.

Them: Cool.

Sounds silly, but it really was that simple. Gone was the tendency to hide the truth from others that reflected my desire to hide it from myself. Gone was the tentativeness and questioning, telling others that I was questioning part of myself–and inviting them to question me, too.

Accepting yourself communicates confidence [and] insulates you from the tide of emotions that wells up whenever other people’s views intersect with your own.

Instead I gained a clear and simple truth, grounded in fact: This is where I’ve worked, and whatever others may think, I still gained some valuable experience from it–experience that helped me make better decisions about my career later on. Ask me about that, and I’d be glad to talk about it.

This way, I consciously remove myself from any possible judgment. And if I am judged negatively, that needs to be wholly owned by the other person–I won’t do their judging for them. The physicist Richard Feynman has said, “You have no responsibility to live up to what other people think you ought to accomplish. I have no responsibility to be like they expect me to be. It’s their mistake, not my failing.”

Accepting yourself communicates confidence, which is a well-known career asset. More than that, it insulates you from the tide of emotions that wells up whenever other people’s views intersect with your own–sometimes muddling your thoughts and bending your beliefs.

What do you do with their views? How do you stop judging yourself? Laugh at it! At least to yourself. A big laugh helps you look deep, examine your self-judgments, and push through the steps to embracing the most (no-longer) cringeworthy parts of your work experience:

H–Hide

A–Apologize

A–Accept

HAA!

Listen, we’re all full of self-judgments: We tell ourselves we’re fat, lazy, don’t exercise enough, aren’t worthy of a raise, aren’t worthy of love, wouldn’t find another job if we were fired or a new significant other if we’re dumped. Those can become dangerously self-fulfilling prophecies if you let them, especially in the job market. Sometimes we forget that we’re all trying our best–all of us–to do better.

It’s a process. And that’s nowhere truer than in our careers; tell yourself you’ve finally “arrived,” and your skills, curiosity, and potential will stagnate in short order.

Find what’s hidden, stop apologizing, and accept yourself. It’s the best thing you can do for your occasionally humiliating resume–and the career you’re rightly proud that it’s led to.

An earlier version of this article originally appeared in Fast Company.

The 3 S’s of Success

“How can I be successful?”

It’s a question many of us ask ourselves and have trouble answering. Because what is success, anyway? Is it writing a book and selling a million copies? Is it winning awards and gaining respect from your peers? Or is just feeling satisfied with your work?

We’re often told that success is in the eye of the beholder — that we need to define it for ourselves, on terms that are meaningful to us.

I believe that’s true but that advice doesn’t tell us how to do it. Try as we might, many of our achievements wind up fitting a mold that suits somebody else — employers, parents, societal expectations — at least as much as, if not more than, it suits us personally. And we still find ourselves left unsatisfied or unhappy, wishing we had something more or something else, no matter how ‘successful’ we’ve been.

I think one of the reasons why is because there roughly are three types of success. I call them the 3 S’s. The trick is to first decide that you can’t have all three of them at once and that you therefore must figure out which one you’re really aiming at.

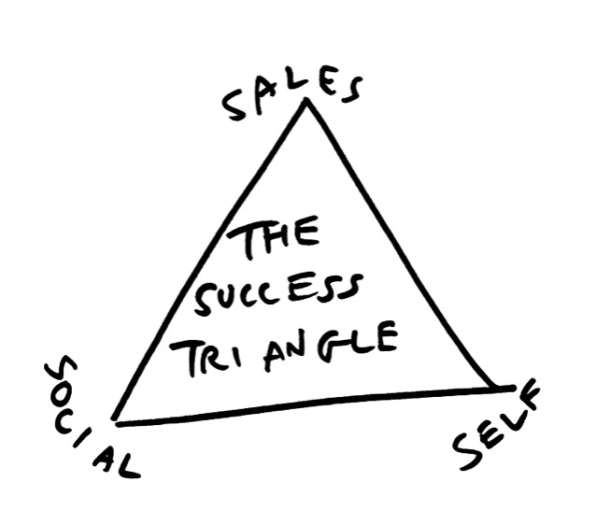

Here’s how I draw the 3 S’s of success on a triangle:

1. Sales success is about getting people to buy something you’ve created. Your book is a commercial hit! Everybody’s reading it, everybody’s talking about it, you’re on TV. You sell hundreds and then thousands and then millions of copies. Dump trucks beep while backing into your driveway before pouring out endless shiny coins as royalty payments. Sales success is about money. How much did you sell?

2. Social success means you’re widely recognized among your peers and people you respect. Critical success. Industry renown! To extend the book example, let’s say the New York Times reviews your latest novel and some writers you respect send you letters saying they thought the book was great (whether or not it’s a commercial hit).

3. Self success is in your head. It’s invisible. Only you know if you have it, because it corresponds to internal measures you’ve established on your own. Self success means you’ve achieved what you wanted to achieve. For yourself. You’re proud and satisfied with your work.

These three categories are broad and approximate but I think that’s why they’re useful: Chances are good that any major achievement you reach will fall more clearly into one than another. They apply to pretty much all industries, professions, and aspects of life.

The point is that success is not one-dimensional.

In order to be truly happy with your successes, you first need to decide what kind of success you want.

Are you in marketing? Sales success means your product flew off the shelves and your numbers blew away forecasts. Social success means you were written up in prestigious magazines, nominated for an award, or shouted out by the CEO at the all-hands meeting. Self success? That’s the same: How do you feel about your accomplishments?

Are you a teacher? Sales success means you’re offered promotions based on your work in the classroom because the bosses want to magnify and implement your work more widely. You’re asked to become a Vice Principal or Principal. Social success means educators invite you to present at conferences, mentor new teachers, and the superintendent recognizes you for your work. Self success? Again: How do you feel about your accomplishments?

There is a catch, though.

I believe it’s impossible to experience all three successes at once.

Picture the triangle above like one of those wobbly exercise planks at an old-school gym. If you push down on two sides, the third side lifts into the air. In our lives and work, it’s rare that any given thing we do — any single success we achieve, no matter how great — can satisfy ourselves and others in equal measure. Aspiring to that, if you ask me, is a mistake.

Sales success, for instance, can block self success. That’s what happened to me as a writer when I got hooked on bestseller lists, blog stats, and brand extensions. Personal goals took a backseat to more tangible commercial ones. I started making things because I was asked to and not because I wanted to. Sure, the saying goes “make hay while the sun shines,” and I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with chasing commercial success, but I’m pointing out that if that’s your north star it can distract or block you from chasing deeply personal goals.

Look at it the other way.

Personal goals don’t necessarily have a marketable strategy so no sales or social success may follow. I’m talking about making that triple-decker chocolate birthday cake you bake for your daughter, the incredible twelfth grade chemistry lesson you put your heart into for weeks, the backyard deck you built with your bare hands. You wouldn’t expect royalty payments or critical reviews from those endeavors. You’re not trying to sell cakes, lesson plans, or decks. You could! But that wasn’t your goal.

And, finally, let’s peek at this from a final view. Critical darlings often sell poorly. You see this almost every year at the Oscars. Spotlight wins Best Picture — tense, dramatic, wonderful acting. How much did it gross at the domestic box office? $45 million. That same year Furious 7 made $353 million.

Which would you have rather made?

There is Sales, Social, and Self success.

Spend time thinking about which one you want and then go.

Good luck!

Take More Pictures: The counterintuitive way to build resilience

When I was researching my book on resilience, I discovered something so obvious it blew me away.

I think I was around nine years old when my dad bought me the Complete Major League Baseball Statistics, a frayed paperback with a green cover. I treasured it and kept it in my room for years. I flipped through it so many times.

As I paged through the numbers, I started noticing something interesting. Cy Young had the most wins of all time in baseball (511). He also had the most losses (316). Nolan Ryan had the most strikeouts (5714), and the most walks (2795).

Why would the guy with the most wins also have the most losses?

Why would the guy with the most strikeouts also have the most walks?

It’s simple—they just played the most.

They tried the most and moved through loss the most.

When everything rests on the numbers

Sometimes, achieving something really is about quantity over quality not the other way around. I’ve asked wedding photographers how they manage to capture such perfect moments. They all say the same type of thing: “I just take way more pictures. I’ll take a thousand pictures over a three-hour wedding. That’s a picture every 10 seconds. Of course I’m going to have 50 good ones. I’m throwing 950 pictures away to find them!”

Sometimes, when I’m doing Q&A after a speech, someone asks me a question along the lines of “So, congratulations on the success of The Book of Awesome. My question is: How do I get paid millions to write about farting in elevators?”

To me, this is like asking, “So you won the lottery. How do I win the lottery, too?”

I always answer the same way, with a reply I stole from Todd Hanson, former head writer at The Onion. He said that whenever someone asks him the question “So how do I get a job writing jokes for money like you did?” he gives a straightforward answer:

“Do it for free for 10 years.”

We cannot hack our way to success

Today, we’re surrounded by tales of companies with million-dollar valuations that grow at lightning-fast rates. We hear about tiny startups that Google acquires for billions of dollars, just a few months after launch. We want to read about the fastest way to get a six-pack or accelerate our careers. But ultimately, what we want to find—quick fixes, easy answers, shortcuts—isn’t there.

Some things take time. They take time. They just take time. It’s not about the number of hits but rather the number of times you step up to the plate. The most important questions to ask yourself are:

Am I gaining experience?

Will these experiences help?

Can I afford to stay on this path for a while?

Sometimes? No. Other times? Yes. And either way you’ll help yourself see that you are learning, doing, and moving—even if that means lots of failure on the way.

“I’m a big fan of poof”

Seth Godin, bestselling author of over 20 books, offered similar advice in an interview with Tim Ferriss: “The number of failures I’ve had dramatically exceeds most people’s, and I’m super proud of that. I’m more proud of the failures than the successes because it’s about this mantra of ‘Is this generous? Is this going to connect? Is this going to change people for the better? Is it worth trying?’ If it meets those criteria and I can cajole myself into doing it, then I ought to.”

And in and interview with Jonathan Fields on Good Life Project, he said, “I’m a big fan of poof.” What’s poof? The idea that you try and if it’s not working—poof. You go try something else.

I’m writing this article as part of my research, lessons, and ideas on resilience in You Are Awesome. That book came out over a year ago now. Is it a hit? Is it a flop? Honestly, it almost doesn’t matter. Because, either way, the only choice I have is to move on to the next thing.

Sure, I want it to succeed. But I can’t determine that. All I get to do is take more pictures. All I get to do is keep going with my next book, next talk, next project, next whatever, whether this one is a hit or goes poof.

You need to do the same.

Success stories are not stories of success

We need to stop looking at successful people with the lens that their lives contain a success that led to a success that led to another success. Because you know what we’re really looking at? Not success, not really. Just people who are just really good at moving through failures.

Moving through failures, swimming through failure, recovering and going forward from failure? That’s the real success. Successful people get to where they’re going because they are willing to try something when the possibility of failure is high … they know and accept that and don’t shy away from it.

So when it comes to long-term success, remember it’s not how many home runs you hit. It’s how many at-bats you take. The wins will only pile up if you keep stepping up to the plate.

This is an edited excerpt from You Are Awesome: How To Navigate Chance, Wrestle with Failure, and Live and Intentional Life

How to Cut All Meeting Time in Half

In November 1955 a strange article appeared in The Economist by an unknown writer named C. Northcote Parkinson. Readers who started skimming the article, titled “Parkinson’s Law,” were met with sarcastic, biting paragraphs poking sharp holes in government bureaucracy and mocking ever-expanding corporate structures. It was searing criticism masked as an information piece. It began innocently enough with the following paragraph:

“It is a commonplace observation that work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion. Thus, an elderly lady of leisure can spend the entire day in writing and dispatching a postcard to her niece at Bognor Regis. An hour will be spent in finding the postcard, another in hunting for spectacles, half-an-hour in a search for the ad dress, an hour and a quarter in composition, and twenty minutes in deciding whether or not to take an umbrella when going to the pillar-box in the next street. The total effort which would occupy a busy man for three minutes all told may in this fashion leave another person prostrate after a day of doubt, anxiety and toil.”

The thesis of the piece was in the first sentence: “It is a commonplace observation that work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” Haven’t we heard advice like this before? “The ultimate inspiration is the deadline,” for instance. “If you leave it till the last minute, it takes only a minute to do.” Or how about: “The contents of your purse will expand to fill all available space.”

Think back to bringing homework home from school on the weekends. There was nothing better than a weekend! But the dull pain of having to do a page of math problems and write a book summary loomed like a faint black cloud over Friday night, all day Saturday, and Sunday morning. I remember I would always work on homework Sunday night. But once in a while, if we were going away for the weekend, if I had busy plans on both days, I would actually get my homework done on Friday night. The deadline had artificially become sooner in my mind. And what happened? It felt great. It felt like I had more time all weekend. A fake early deadline created more space.

How do you cut all meeting time in half?

As part of a job I had at Walmart years ago I suddenly took ownership over the company’s weekly meeting for all employees. It was a rambly Friday-morning affair without a clear agenda, presentation guidelines, or timelines, all in front of 1000 people. The CEO would speak for as long as he wanted about whatever he wanted and then pass the mic to the next executive sitting at a table, who would speak as long as he wanted about whatever he wanted, before passing the mic to the next person. It was unpredictable—and starting at 9:00 a.m., it rolled into 10:00 a.m., sometimes 10:30 a.m., and occasionally 11:00 a.m. People would go on tangents. Nobody was concise. And everyone would leave two hours later in a daze, trying to remember all the mixed priorities they heard at the beginning of the meeting.

So I worked with the CEO to redesign the meeting. We created five segments of five minutes each and set up an agenda and schedule of presenters in advance. “The Numbers,” “Outside Our Walls,” “The Basics 101,” “Sell! Sell! Sell!” and “Mailbag,” where the CEO opened letters and answered questions from the audience.

The new meeting was twenty-five minutes long!

And it never went over time once.

How come?

Because I downloaded a “dong” sound effect that we played over the speakers with one minute left, a “ticking clock” sound effect that played with fifteen seconds left, and then the A/V guys actually cut off a person’s microphone when time hit zero. If you hit zero, you would be talking onstage but nobody could hear you. You just had to walk off.

What happened?

Well, at first everybody complained. “I need seven minutes to present,” “I need ten minutes,” “I need much, much longer because I have something very, very important to say.” We said no and shared this quote from a Harvard Business Review interview with former GE CEO Jack Welch:

“For a large organization to be effective, it must be simple. For a large organization to be simple, its people must have self-confidence and intellectual self-assurance. Insecure managers create complexity. Frightened, nervous managers use thick, convoluted planning books and busy slides filled with everything they’ve known since childhood. Real leaders don’t need clutter. People must have the self-confidence to be clear, precise, to be sure that every person in their organization—highest to lowest—understands what the business is trying to achieve. But it’s not easy. You can’t believe how hard it is for people to be simple, how much they fear being simple. They worry that if they’re simple, people will think they’re simpleminded. In reality, of course, it’s just the reverse. Clear, toughminded people are the most simple.”

Then what happened?

Well, with a clear time limit, presenters practiced! They timed themselves. They prioritized their most important messages and scrapped everything else. They used bullet points and summary slides. We introduced the concept by saying “If you can’t say it concisely in five minutes, you can’t say it. By then people doze off or start checking their email.” Have you ever tried listening to someone talk for twenty straight minutes? Unless they are extremely clear, concise, and captivating, it’s a nightmare.

Everybody got a bit scared of their mic cutting off, so the meetings were always twenty-five minutes.

What happened to productivity?

Well, a thousand people saved an hour every week. That’s 2.5% of total company time saved with just one small change.

How do you complete a three-month project in one day?

Sam Raina is a leader in the technology industry. He oversees the design and development of a large website with millions of hits a day. He has more than sixty people working for him. It’s a big team. There are many moving parts. From designers to coders to copy editors. How does he motivate his team to design and launch entirely new pages for the website from scratch?

He follows Parkinson’s Law and cuts down time.

He books his entire team for secret one-day meetings and then issues them a challenge in the morning that he says they’re going to get done by the end of the day. There is only one day to make an entire website! From designing to layout to testing—everything.

Everyone freaks out about the deadline. And then everyone starts working together.

“The less time we have to do it, the more focused and organized we are. We all work together. We have to! There is no way we’d hit the deadline otherwise. And we always manage to pull it off,” Sam says.

By spending a day on a project that would otherwise take months, he frees up everyone’s thinking time, transactional time, and work time. There will be no emails about the website, no out-of-office messages, no meetings set up to discuss it, no confusion about who said what. Everyone talks in person. At the same time. Until it’s done! Sure, in-person isn’t easy in a pandemic, but what meetings are you doing that right that are laddering up into other meetings which are laddering up into other meetings? How can more people be brought together on a larger problem to avoid all the friction in between?

So what’s the counterintuitive solution to having more time?

Chop the amount of time you have to do it.

Look at the left of the graph. The less time available, the more effort you put in. There is no choice. The deadline is right here. Think of how focused you are in an exam. Two hours to do it? You do it in two hours! That deadline creates an urgency that allows the mind to prioritize and focus.

Now look at the right of the graph. The more time available, the less effort we put in overall. A little thought today. Start the project tomorrow. Revisit it next week. We procrastinate. Why? Because we’re allowed to. There is no penalty. Nothing kills productivity faster than a late deadline.

What does C. Northcote Parkinson say about waiting to get it done?

“Delay is the deadliest form of denial,” he says.

Have you ever finished a project on time and then the teacher announces to the class that the deadline has been extended? What a bummer. Now, even though you finished at the original deadline, you get the pain and torture of mentally revisiting your project over and over again until you hand it in. Could it be better? How can we improve it?

Calvin says it best:

Remember: Work expands to fill the time available for its completion.

In the around-the-table weekly Zoom call, in the original 1000 person company meeting, in a normal website-development cycle, what invisible liability do you find? Time. Too much of it.

And work expanding to fill it as a result.

What’s the solution?

Create last-minute panic!

Move deadlines up, revise them for yourself, and remember you are creating space after the project has been delivered.

Do only nerds do their homework Friday night?

Maybe.

But they’re the ones with the whole weekend to party.

This article is adapted from The Happiness Equation

Jack Welch quote is excerpted from “Speed, Simplicity, Self-Confidence: An Interview with Jack Welch” by Noel M. Tichy and Ram Charan, Harvard Business Review, September 1989. Used with permission.

Calvin and Hobbes strip is © 1992 Watterson and reprinted with permission of Universal Uclick. All rights reserved.

Figure out your dream job by asking yourself this question

In the late 1990s I began an undergrad business degree program at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. After nearly flunking Economics 101 and striking out with a majority of sports and teams, I finally found my home among a group of interfaculty misfits at the Golden Words comedy newspaper.

Golden Words was the largest weekly humor newspaper in the country, an Onion-esque paper publishing 25 issues per year, with a new issue every Wednesday during the school year. For the next four years, I spent every Sunday hanging out with a group of people writing articles that made us all laugh. We got together around noon and wrote until the wee hours of Monday morning. I didn’t get paid a cent, but the thrill of creating, laughing, and seeing my work published gave me a great high.

I loved it so much that I took a job working at a New York City comedy writing startup during my last summer of college. I rented an apartment on the Lower East Side and started working in a Brooklyn loft with writers from The Simpsons and Saturday Night Live. “Wow,” I remember thinking, “I can’t believe I’m getting paid to do what I love.”

But it was the worst job of my life.

Why your dream job could be the worst job you ever have

Instead of having creative freedom to write whatever I wanted, I had to write, say, “800 words about getting dumped” for a client like Cosmopolitan. Instead of joking with friends naturally and finding chemistry writing with certain people, I was scheduled to write with others. Eventually my interest in comedy writing faded, and I decided I would never do it for money again.

When I started writing my blog 1000 Awesome Things in 2008, I said I’d never put ads on the website. I knew the ads would feel like work to me, and I worried that I might self-censor or try to appeal to advertisers. No income from the blog meant less time trying to manage the ads and more time focused on the writing, I figured.

I was smart about that… but not smart enough to ignore the other extrinsic motivators that kept showing up: stat counters, website awards, bestseller lists. It was all so visible, so measurable, and so tempting. Over time I found myself obsessing about stat counters breaking 1 million then 10 million then 50 million, about the book based on my blog staying on bestseller lists for 10 weeks then 100 weeks then 200 weeks, about book sales breaking five figures then six figures then seven figures. The extrinsic motivators never ended, and I was slow to realize that I was burning myself out. I was eating poorly, sleeping rarely, and obsessing about whatever next number there was to obsess about.

I started worrying that the cycle — set goal, achieve goal, set goal, achieve goal, set goal, achieve goal — would never end. And I started forgetting why I started writing my blog in the first place. I was shaken by how quickly I had gotten caught up in the achievement trap.

Studies show that when we begin to value the rewards we get for doing a task, we lose our inherent interest in doing the task. The interest we have becomes lost in our minds, hidden away from our own brains, as the shiny external reward sits front and center and becomes the new object of our desire.

Keep in mind that there are two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic is internal — you’re doing it because you want to. Extrinsic is external — you’re doing it because you get something for it. Teresa Amabile, a professor at Harvard Business School, has performed some experiments on intrinsic and extrinsic motivators with college students. She asked the students to make “silly collages” and invent stories for them. Some were told they were getting rewards for their work, and some were not. What happened? Based on scores from independent judges, the least creative projects by far were done by students who were promised rewards for their work. Amabile said, “It may be that commissioned work will, in general, be less creative than work that is done out of pure interest.”

And it’s not just getting rewards that hurts quality. In another study conducted by Amabile, 72 creative writers at Brandeis University and Boston University were split into three groups of 24 and asked to write poetry. The first group was given extrinsic reasons for doing so — impressing teachers, making money, getting into fancy grad schools. The second group was given a list of intrinsic reasons — enjoying the feeling of expressing themselves, the fun of playing with words. The third group wasn’t given any reason. On the sidelines, Amabile put together a group of a dozen poet-judges, mixed up all the poems, and had the judges evaluate the work. Far and away, the lowest-quality poems were from those who had the list of extrinsic motivators.

James Garbarino, former president of the Erikson Institute for Advanced Study in Child Development, was curious about this phenomenon. He conducted a study of fifth- and sixth-grade girls hired to tutor younger children. Some of the tutors were offered free movie tickets for doing a good job. What happened? The girls who were offered free movie tickets took longer to communicate ideas, got frustrated more easily, and did a worse job than the girls who were given nothing except the feeling of helping someone else.

The Garbarino study raises the question: Do extrinsic motivators affect us differently depending on age? Do we grow into this pattern — and can we grow out of it? According to a recent study by Felix Warneken and Michael Tomasello, we may be hardwired to behave this way. Their work found that if infants as young as 20 months are extrinsically rewarded after helping another infant, they are less likely to help again than infants who received either no reward or simple social praise.

The secret to avoiding burnout

I was surprised by the studies, but they made sense to me. I loved writing for Golden Words. It was a joy, a thrill, a true love. With the paid writing startup in New York City, I lost all my energy and drive.

When you’re doing something for your own reasons, you do more, go further, and perform better. When you don’t feel like you’re competing with others, you compete only with yourself. For example, Professor Edward Deci of the University of Rochester conducted a study where he asked students to solve a puzzle. Some were told they were competing with other students and some were not. You can probably guess what happened. The students who were told they were competing with others simply stopped working once the other kids finished their puzzles, believing themselves to be out of the race. They ran out of reasons to do the puzzle. But those who weren’t told they were competing with others kept going once their peers finished.

Does all this mean you should just rip up your paycheck and work only on things you’re intrinsically motivated to do? No. But you should ask yourself, “Would I do this for free?” If your answer is yes, you’ve found something worth working on. If the answer is no, let paid work remain paid work and keep asking yourself what you would do simply for the pleasure you derive from doing it. Chances are, if you’re working solely for extrinsic reasons such as money, you’re bound to burn out sooner or later.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Harvard Business Review

The Most Surprising Advice On Success I Received From A Harvard Dean

Ever suck at what you’re doing?

Of course you do. We all do! We sign up for things we don’t start. We start things we don’t finish. We end up somewhere and look around with no idea how we got there.

Maybe you moved to a neighborhood where everybody is way richer than you and has a fancier car. You took a job at a company where everybody speaks in codes you don’t understand.

You got married and had a child with someone you’re not sure you like. We make mistakes. Part of living is putting ourselves in new situations but sometimes these situations are wildly uncomfortable or end badly. Sometimes you just want to press the eject button and blast off to Mars.

That’s how I felt for much of my time at Harvard. I respected the school, I was wowed by the professors, I loved my classmates, but I just didn’t relate to the careers I saw grads heading toward.

Why would I want to sit in a windowless boardroom helping a rich company get richer by telling them how to fire ten thousand people? Why would I want to help two companies merge just to satisfy some billionaire CEO’s ego? Why would I want to slave away on a marketing team desperate to sell the world more air fresheners?

These jobs made no sense!

But then again... they paid so much money. If the world is built on gears and cranks, a lot of these jobs were spinning them.

I felt I wanted the lifestyle the school was leading me toward but at the same time it didn’t make sense to me.

This is the context when I heard a story from Dean John McArthur that resonated deeply and which I think about every time I’m trying to get stronger.

Let me share it now.

The life-changing story from the dean

When I got into Harvard Business School they asked to see my tax returns from the past three years to assess me for financial aid. So I gathered all the paperwork. And my income added up to less than $50,000... total... for three years.

Why?

Well, I’d scored a doughnut three years earlier because I was still a college student. And I’d scored another doughnut when I was running my restaurant and couldn’t afford to take a salary.

And between those two goose eggs was my Procter & Gamble salary of $51,000 plus bonus. Or at least part of it, since I hadn’t made it through a full year there.

I was embarrassed sending in the numbers to Harvard but delighted a couple months later when I got a letter in the mail saying “Congratulations! You are so poor we are going to pay for you to come here!”

Finding out I suddenly didn’t need $70,000 of student loans felt like I’d just won the Powerball. But I’d received a lot of phone calls offering me free Caribbean cruises over the years so I read the letter again to make sure it was legit.

Turns out it was legit.

Turns out me and many other Canadian students were recipients of the John H. McArthur Canadian Fellowship.

John McArthur was the dean of Harvard Business School from 1980 to 1995 and, a Canadian himself, he established a fellowship to pay tuition for any Canadian who got into the school and wasn’t sitting on wads of cash.

I felt an incredible swell of love for this random old man who I had never met, so when I got to Harvard I spent an entire night writing a five page thank-you letter sharing my life story, my failures, everything that had led me to this point, and everything I wanted to do afterward.

Before I could second guess whether he wanted a super-long letter from a total stranger, I sealed it with a kiss and dropped it in a mailbox in Harvard Square.

A few weeks later I got a phone call from John McArthur’s office inviting me to lunch with the sugar daddy himself!

I must have sounded nervous on the phone because the assistant had to calm me down. “Don’t worry,” she said. “He’d just like to meet you.” Then she whispered, “We don’t get many five-page thank-you letters.”

So between classes a couple weeks later, I found John McArthur’s office behind tall oak trees in a vine-covered building in a corner of campus.

I was escorted in. He swiveled around on his desk chair, smiled, got up, and shook my hand.

“Neil, have a seat,” he said, and gestured toward the circular table in the middle of the room, where two boxed sandwiches were sitting.

“Hope you like tuna.”

He patiently waited for me to choose from the many chairs to sit on and then picked the chair right beside me. He was wearing a casual button-up cardigan and thick glasses that wobbled on his nose. And he smiled so warmly, like an old friend—humble, gracious, down to earth.

I found this especially amazing as there seemed to be an incredibly famous painting on the wall behind him. Was that a Picasso?

He caught me looking at it. “Oh, that,” he said. “Some foreign leader gave it to us as a present. We couldn’t put it up in the dean’s residence on account of the, uh...”

I stared at the picture as his voice trailed off and noticed it looked like a painting of a bull sporting a gigantic blue boner.

I laughed and we started chatting.

“So, how’s school going so far?” he asked.

“Oh, you know, stressful. We started classes a few weeks ago, and I’m up past midnight every night reading cases and preparing for them. And the companies have already started visiting campus. Everybody wants to work at the same five places, so we’re chugging beers with millionaire consultants and bankers with black bags under their eyes hoping we can become millionaire consultants and bankers with black bags under our eyes, too.”

He raised his eyebrows and laughed.

There was a pause.

And then he told me a story that changed my life and, looking back, was worth more to me than all the tuition he was so generously covering for me.

So get off the beach

“Neil, right now you’re just an eager guy standing outside the beach,” he began. “You’re standing at the fence looking in. The beach is closed, but it’s opening soon. You can see the sand, you can smell the ocean, you can see a half-dozen beautiful people sunbathing in bathing suits. But you know who’s beside you at the fence? A thousand other eager folks just like you. They’re all eager. They’re all gripping that fence. They all want on that beach. And when the door to the fence opens, they’re all running on to the hot sand and trying to seduce the same few sunbathers. Your odds of winning any of them over are so low.”

I nodded. I had been through campus recruiting at Queen’s.

It was painful. Hundreds of hours researching companies, tailoring resumes, writing cover letters, filling out online applications, doing practice interviews, buying clothes for interviews, researching all the interviewers before I met them, writing and sending thank-you notes, and then the giant stress of waiting weeks or months for replies.

“So get off the beach,” he said.

“Let the thousand other folks run in and fight each other. Let them bite and claw and scratch each other. And sure, let a few of them win over one of those few sunbathers. But it’s much better to get off the beach. Because even if you happen to win, do you know what you would be doing the whole time on that beach? Looking over your shoulder. Seeing who else is going to stake their claim and send you packing. You probably won’t win in any case. But if you do, you win a life full of stress.”

I was in a state of permanent anxiety on campus. I was anxious about classes because I was anxious about grades and I was anxious about grades because I was anxious about jobs and I was anxious about jobs because I was anxious about money.

And here was this man offering relief.

“But if I don’t land one of those jobs,” I said, “I’ll be broke. I got your fellowship because I didn’t have any money. I was hoping to correct that problem.”

He laughed.

“You’ll be fine. It’s simple economics. There are far more problems and opportunities in the world than there are talented and hard-working people to solve them. The world needs talent and hard work to solve its problems so people with talent who are hard workers will have endless opportunities.”

His words felt like calamine lotion rubbed on the bright red burn itching at the center of my soul. What he was saying was... different.

“So,” I asked him, cautiously furthering the metaphor, “if I leave the beach, where do I go?”

“What do you think you offer?” he asked. “You’re young. You have little experience. But you’re learning. You’re passionate. You give people energy and ideas. And who needs that? Not the fancy companies flying here in private jets. It’s the broken companies. The bankrupt companies. The ones losing money. The ones struggling. They need you. The last thing they’re doing is flying teams to Harvard recruiting sessions. But if you knock on their doors and if you get inside, then they will listen to your ideas, give you big jobs with lots of learning, and they’ll take you seriously. You’ll participate in meetings instead of just taking notes. You’ll learn faster, gain experience quicker, and make changes to help a place that actually needs help.”

There was a long pause as I digested what I was actually hearing.

Think about this for a second.

Harvard Business School had an army of people dedicated to planning, executing, and guiding students through campus recruiting. It was a giant department. Career visioning workshops. Job posting boards. Information sessions. Beer nights and company dinners. First, second, third round interviews on campus. And here I was sitting in front of the Dean who was telling me to set a match to it all. Ignore it completely and call up a pile of broken and bankrupt places. I left that lunch and never applied for another job through the school again. Not a single info session, not a single job posting, not a single interview. I just went back to my apartment and made an Excel spreadsheet. I filled it with a list of all the broken, beaten down companies I could think of. Places that were doing something interesting but had fallen on hard times. A big oil spill. A plummeting stock price. A massive layoff. A failed launch. A big PR problem.

Reputation in the toilet.

I came up with about a hundred company names. I then wrote up a 30-second cold call script saying I was a student studying leadership and would love to ask a couple questions to a leader in Human Resources. I cold called all hundred companies.

I got in the door with maybe half of them and then followed up with them to say thank you, share a couple articles, and ask to meet for coffee or lunch. About a dozen took me up on the offer.

And after those dozen conversations, I wrote thank you letters and followed up asking for a summer job.

I got five offers.

And all five were from companies off the beach.

I took a job at Walmart and found I was the only person with a master’s degree... in an office of over a thousand people.

Dean McArthur’s advice paid off. I was suddenly a big fish in a small pond. All my peers from Harvard were long gone. They were crunching Excel spreadsheets in glass towers. I was sitting on ripped chairs beside piles of old cardboard boxes in a low-rise building in the burbs.

But I loved it. I had work to do. I had real problems to solve.

At Walmart I found I was one of a handful of people quoting fresh research and case studies since I’d just read and reviewed so much at school. There was a ton I didn’t know. I had no retail experience! No store operations experience! No Walmart experience! But the things I did know were different from what my colleagues knew.

And different is better than better.

I spent the summer designing, planning, and running the first internal leadership conference at the company.

It was a hit.

Then, on my last day of the summer job, the head of HR handed me a full-time job offer with a primo starting salary pasted on top.

I was way off the beach.

And it felt great.

What’s wrong with the $5 million condo?

What did I learn from Dean McArthur’s beach story?

Find the small ponds so you can be the big fish. When I was at Harvard Business School I was below average in everything. Grades, class participation, whatever you were measuring, I was in the bottom half. I was a little fish in a big pond of high achievers from around the world. I never felt great about what I was accomplishing there. I was always on the low end of the totem pole. I think about this a lot when I see ads on the inside covers of fancy magazines advertising new Manhattan condos starting at $5 million. That’s a little fish in a big pond right there! $5 million means you have the worst condo in the entire building. No view, no prestige, no nothing. Who would drop money on that kind of pain when $5 million could buy you a penthouse suite almost anywhere else?

When I started at Walmart, I was different. And different really is better than better.

My degree wasn’t immediately neutralized by being rounded by tables of people with fancy degrees. At Walmart, I was worth something. So my confidence went up. My “I can do this!” feeling rose and rose and rose.

Don’t start swimming in the biggest pond you can find. Start in the smallest. Don’t chase the hot guy or hot girl at the beach. Find the nerd at the library. Find the broken company.

Find the place nobody wants to be.

And start there.

Dean McArthur’s advice worked so well for me I started using it in other areas of my life, too.

Sometimes it was conscious.

Sometimes it wasn’t.

But it always worked.

When I began doing paid keynote speeches, my speaking agency suggested a starting fee range that seemed super high to me.

“Summarize everything you’ve learned from your research and experiences in an hour, fly wherever people want you to be, deliver it all live in front of a thousand people, and make sure you’re entertaining, educational, and empowering. It’s a hard job! You should be paid well for it.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “That seems too high. Who else is in that range?”

They listed a slew of people. New York Times bestselling authors, gold medal–winning Olympians, rock star professors. I’d heard of them all.

“Hmm,” I said. “What about half that price?”

They listed a bunch of people I’d never heard of before.

“And what about half that?” I asked.

“There is no half that,” they said. “That’s the lowest range. It doesn’t make sense for us to work for months and spend hours on conference calls and manage all logistics for commissions on speeches below a certain level.”

“Okay,” I said. “Start me at your lowest range, please.”

The agency didn’t love it but by giving speeches at a lower price I got booked for smaller conferences and events. I was in local boardrooms with fifty people instead of Vegas casinos with a thousand. My confidence went up. And it stayed up as I moved onto bigger stages.

I looked into the research underpinning the small pond line of thinking, and it turns out it’s only thirty years old. Back in 1984 a study by Herb Marsh and John W. Parker appeared in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. It asked a very simple and incisive question: “Is it better to be a relatively large fish in a small pond even if you don’t learn to swim as well?”

The research in the study provided the clear answer.

Yes.

It is.

That study was the lead domino in a slew of studies around the globe that confirmed the same incredible result.

Regardless of age, socioeconomic background, nationality, or cultural upbringing, when you’re in a smaller pond, your opinion of yourself what’s called “academic self-concept”—goes up. And importantly, it stays up even after you leave the pond. This is because two opposing forces present themselves: fitting into the group you’re with and a contrasting belief of feeling “better than this group.” Our brains like that second feeling, and it sticks with us as we realize “Hey, I can do this” or “Hey, I can maybe do better than this.”

What’s another way to think about it?

Ask yourself one key question.

Would you rather be a 5 in a group of 9s, a 9 in a group of 9s, or a 9 in a group of 5s?

The most impressive results of these studies say that being a 9 in a group of 5s increases your positive academic self-concept even ten years after you leave the group.

Put yourself in a situation where you think you’re a big deal.

Guess what? You’ll think you’re a big deal for a long, long time.

And the studies saw these results across a wide range of countries in both individual and collectivist cultures around the globe.

So I say there’s no shame putting yourself in situations where you feel really good about yourself. Should you downgrade yourself? No! Definitely no. But there’s nothing wrong with entering the marathon in the slowest category. Playing in the house league instead of the rep league. Teeing off from the tee closest to the pin.

You know what you’re doing?

Setting yourself up for success.

You’ll move up because you believe in yourself.

Now, is there a danger here? Can you think you’re such a big a deal that you damage relationships or hurt others? Yes! That’s the fire we’re playing with. Do you ever wonder why so many celebrities get divorced after they first become famous? Maybe it’s because their academic self-concept skyrocketed! They think they’re a huge fish! And suddenly the small pond marriage they’re in feels way too small. So they jump into a bigger pond and date a superstar.

Why do I mention this? Because it’s about self awareness.

We have to be aware of which pond we’re swimming in and be kind as we swim. Finding small ponds isn’t an excuse to act arrogantly and feel boastful. We’re not trying to spike volleyballs into kindergarten foreheads here.

We’re using a proven science-backed way to be kind to ourselves, swim in the shallows, and help ourselves slowly, slowly, slowly get all the way up to awesome.

Find small ponds.

This article is an excerpt from my new book You Are Awesome

You Need To Take More Vacation … And Here’s How To Do It

Mandatory vacation is the way of the future

Have you ever felt burned out after a vacation?

I’m not talking about being exhausted from fighting with your family at Disney World all week. I’m talking about how you knew, the whole time walking around Epcot, that a world of work was waiting for you upon your return.

Our vacation systems are completely broken.

They don’t work.

The classic corporate vacation system goes something like this: You get a set number of vacation days a year (often only two to three weeks), you fill out some 1996-era form to apply for time off, you get your boss’s signature, and then you file it with a team assistant or log it in some terrible database. It’s an admin headache. Then most people have to frantically cram extra work into the weeks before they leave for vacation in order to actually extract themselves from the office. By the time we finally turn on our out-of-office messages, we’re beyond stressed, and we know that we’ll have an even bigger pile of work waiting for us when we return.

What a nightmare.

For most of us, it’s hard to actually use vacation time to recharge.

So it’s no wonder that absenteeism remains a massive problem for most companies, with payrolls dotted with sick leaves, disability leaves, and stress leaves.

In the UK, the Department for Work and Pensions says that absenteeism costs the country’s economy more than £100 billion per year. A white paper published by the Workforce Institute and produced by Circadian, a workforce solutions company, calls absenteeism a bottom-line killer that costs employers $3,600 per hourly employee and $2,650 per salaried employee per year. It doesn’t help that, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the United States is the only country out of 21 wealthy countries that doesn’t require employers to offer paid vacation time. (Check out this world map on Wikipedia to see where your country stacks up. We love you, Enlightened Swedes!)

Now.

Let’s solve this problem.

First question is this big one.

Would it help if we got more paid vacation?

No, not necessarily.

According to a study from the U.S. Travel Association and GfK, a market research firm, just over 40% of Americans plan not to use all their paid time off anyway. It’s not the amount we’re given then, it’s the amount we’re taking, or feel able to take.

So what’s the progressive approach?

Is it the Netflix or Twitter policies that say take as much vacation as you want, whenever you want it? Open-ended, unlimited vacation sounds great on paper, doesn’t it? Very progressive, right? No, that approach is broken too.

What happens in practice with unlimited vacation time? Warrior mentality. Peer pressure. Social signals that say you’re a slacker if you’re not in the office. Mathias Meyer, the CEO of German tech company Travis CI, wrote a blog post about his company abandoning its unlimited vacation policy:

“When people are uncertain about how many days it’s okay to take off, you’ll see curious things happen. People will hesitate to take a vacation as they don’t want to seem like that person who’s taking the most vacation days. It’s a race to the bottom instead of a race towards a well rested and happy team.”

The point is that in unlimited vacation time systems, you probably won’t actually take a few weeks to travel through South America after your wedding, because there’s too much social pressure against going away for so long. Work objectives, goals, and deadlines are demanding. You look at your peers and see that nobody is backpacking through China this summer, so you don’t go either. You don’t want to let your team down, so your dream of visiting Machu Picchu sits on the shelf forever.

What’s the solution?

Recurring, scheduled mandatory vacation.

Yes, that’s right — an entirely new approach to managing vacation. And one that preliminary research shows works much more effectively.

Designer Stefan Sagmeister said in his TED talk, “The Power of Time Off,” that every seven years he takes one year off. He said: